Friday, February 24, 2023

The comic genius of Jan van Haasternen

Friday, January 27, 2023

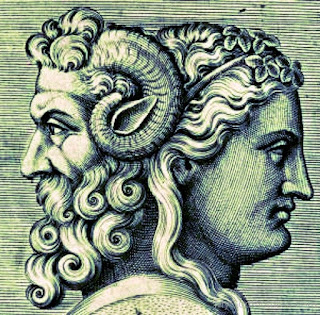

'One face of Janus holds no proportion to the other'.

'In philosophy where truth seems double-faced there is no man more paradoxical than myself, but in Divinity I love to keep the road. [3]

A few paragraphs later utilizing highly original proper-name symbolism, he states -

'yet I perceive the wisest heads stand like Janus in the field of knowledge'. [4]

in other words, the true intellect respects the wisdom of the past as well as advancing knowledge for future generations.

The agenda of Browne's subsequent publication, the encyclopedic endeavour known as Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646-72) was to challenge and refute many of the superstitions and folk-lore beliefs prevalent in his day in favour of reason, experience and 'occular observation'. This included a rejection of medical cures through amulets or 'magical' stones, of which the physician wittily remarks-

'he must have more heads than Janus, that makes out half of those virtues ascribed unto stones and their not only medical, but magical properties, which are to be found in Authors of great name'. [5]

The Roman god Janus is also employed by Browne as a literary 'conjoining' symbol which ingeniously unites his philosophical discourses Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus (1658).

Thematically structured upon the metaphysical templates of Time (Urn-Burial) and Space (The Garden of Cyrus) and highly polarised in their imagery, respective truth and literary style, Browne's twin Discourses remain unique in World literature. In Urn-Burial the gloomy, stoical and funerary half of the literary diptych, the learned physician laments -

'We cannot hope to live so long in our names, as some have done in their persons, one face of Janus holds no proportion unto the other'. [6]

In other words, everyone has either a greater or lesser proportion of their life remaining, no-one can ever know with certainty when they have arrived at an equidistant point between birth and death in their life. The past and the future are unequal in the lives of all through the unknowingness of the human condition.

The Roman god Janus is also encountered in the esoteric discourse The Garden of Cyrus in which, with typical subtle humour he declares -

'And in their groves of the Sun this was a fit number, by multiplication to denote the days of the year; and might Hieroglyphically speak as much, as the mystical Statua of Janus in the Language of his fingers. And since they were so critical in the number of his horses, the strings of his Harp, and rays about his head, denoting the orbs of heaven, the Seasons and Months of the Year; witty Idolatry would hardly be flat in other appropriations'. [7]

Ever helpful to his reader, there's an explanatory foot-note- 'Which King Numa set up with his fingers so disposed that they numerically denoted 365'. i.e. Numa reformed the Roman calendar.

The Roman god Janus is though little recognised, one of several 'conjoyning' proper-name symbols which Browne utilizes in order to unite his philosophical discourses Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus (1658).

A primary source of information about the Roman god Janus can be found in Ovid's Fasti (Festivals). Over a dozen books by the Roman poet Ovid (43 BCE - 17 CE) including several editions of Ovid's Metamorphoses are listed as once in Thomas Browne and his eldest son Edward's combined libraries.[8]

The opening page of Ovid's Fasti narrates firstly of how the poet encounters and questions Janus, the poet reminding his reader that there is no equivalent to Janus in the Greek pantheon of gods -

'Yet what god am I to call you, biformed Janus ? / For Greece has no deity like you'.

Janus subsequently informs the poet of his origins and attributes thus-

'The ancients (since I'm a primitive thing) called me Chaos.

Then I, who had been a ball and a faceless hulk,

Got the looks and limbs proper to a god.

Now as a small token of my once confused shape,

My front and back appear identical....

Whenever you see around, sky, ocean, clouds, earth,

They are all closed and opened by my hand.....

Just as your janitor seated by the threshold

Watches the exits and the entrances,

So I the janitor of the celestial court

Observe the East and West together'.

The celestial 'janitor' who has the power to open and to close is defined as the god of mysteries in general by Ovid who recounts one of the few surviving myths known of Janus. Ovid tells of a deceitful nymph called Carna whom many lovers pursued, but all in vain.

'A young man would declare words of love to her,

And her immediate reply would be:

''This place has too much light and the light causes shame.

Lead me to a secluded cave, I'll come''.

He naively goes ahead; she stops in bushes

And lurks, and can never be detected.

Janus had seen her. Clutched by desire at the sight,

He deployed soft words against her hardness.

The nymph, as usual, demands a more remote cave,

Trails at her leader's heels and deserts him.

Fool ! Janus observes what happens behind his back

You fail; he sees your hideout behind him.

You fail, see, I told you: as you hide by that rock,

He grabs you in his arms and works his will.

'For lying with me,' he says, 'take control of the hinge;

Have this prize for your lost virginity'. [8]

The primary attributes of Janus are hindsight, the ability to learn from past events and foresight, the ability to anticipate future events. These attributes may have contributed in no small measure towards the continuity of Roman civilization on both an individual and collective basis. The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius (121 -180 CE) in his stoical Meditations (listed as once in Browne's library) gives Janus-like advice his reader-

'Look closely at the past and its changing Empires, and it is possible to foresee the things to come'. [9]

'In ancient poetry these souls were signified by the double-headed Janus, because, being supplied like him with eyes in front and behind, they can at the same time see the spiritual things and provide for the material'.

Browne was a pioneering scholar of comparative religion, that is, the study of religious beliefs, their doctrines and symbols, alongside their spread and influence in the world. Assisting him in his study were six modern languages which he was fluent in, as well as Greek, Latin and Hebrew. Although at times misguided in his study, Browne's tolerance and broad-mindedness in religious studies, paved the way for future scholars.

As stated earlier, Janus is exclusively a Roman god without a Greek equivalent. It was not until the eighteenth century that the British philologist Sir William James (1746-94) detected linguistic similarities between Sanskrit and Latin which indicated that Janus originated from the Indian elephant-headed god Ganesh. Its highly probable that Roman merchants who travelled to India for luxury goods such as saffron introduced and modified the Indian god to the Roman world.

Late in his life Browne wrote, though never published, an advisory for the benefit of his children known as Christian Morals it was published posthumously (1716). Equal in testimony to Religio Medici in its adherence to the Christian faith; nevertheless mention of alchemy and astrology along with Hermes Trismegistus can also be found within its pages.

The name of Janus occurs no less than four times in Christian Morals, primarily in the guise as a moral figure advising the reader to learn from hindsight and to develop foresight in their life. Browne first links the temple of Janus in ancient Rome whose doors were shut during peace-time and open during times of war to individual temperament, cautioning his reader to -

'keep the Temple of Janus shut by peaceable and quiet tempers' [10]

Next, he advises, when in doubt to opt for virtue-

'In bivous theorems and Janus-faced doctrines let virtuous considerations state the determination.' [11]

The stoic moralist also instructs his grown-up children to-

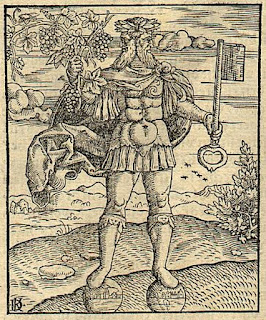

'Let the mortifying Janus of Covarrubias be thy daily thoughts'' [12]

with the explanatory footnote -

'Don Sebastian de Covarrubias writ 3 Centuries of moral emblems in Spanish. In the 88th of the second century he sets down two faces averse, and conjoined Janus-like, the one gallant beautiful face, the other a death's head face, with this motto out of Ovid's Metamorphosis Quid fuerim quid simque vide'. ('See what I was and what I am now').

Lastly, juxtaposing Roman mythology to Biblical scripture in vivid imagery, he declares-

'What is prophetical in one age proves historical in another, and so must hold on unto the last of time; when there will be no room for prediction, when Janus shall lose one face, and the long beard of time shall look like those of David's servants, shorn away upon one side.' [13]

The Old Testament book of Samuel recounts-

'Wherefore Hanun took David's servants, and shaved off the one half of their beards, and cut off their garments in the middle, even to their buttocks, and sent them away'. [14]

The Biblical figure of King David is now believed to have lived circa 1010–970 BCE. Its worthwhile remembering that the King James Bible (1611) with its soaring strophes, rhythmic cadences and striking parallelisms was the predominant influence upon Browne's spirituality. Freshly translated from Hebrew by a host of scholars, the text of the King James Bible was, in all probability, the first book which young Thomas learnt to read as a child. Subsequently it formed a powerful influence upon his literary style as an adult.

Browne's own Janus-like ability to 'foresee' the future is testified in a memoir by the Reverend Whitefoot. The Heigham-based priest was a close friend from the newly-qualified physician's arrival to Norwich in 1637 until 1682 when, upon his death-bed Browne gave 'expressions of dearness' to his long-time friend.

Reverend Whitefoot's memoir includes the following character testimony-

'Tho' he were no prophet, nor son of a prophet, yet in that faculty which comes nearest it, he excelled, i.e. the stochastick, wherein he was seldom mistaken, as to future events, as well publick as private; but not apt to discover any presages or superstition'.

Even greater testimony to Browne's ability to prognosticate the future can be found in the miscellaneous tract known as 'A Prophecy concerning the future state of several nations'. Imitative of the opaque verse of Nostradamus, the 'Prophecy' consists of a series of couplet verse 'predictions', several on America. In Browne's proper-name symbolism America is invariably equated with the new, exotic and unexplored, a good example occurring in Pseudodoxia Epidemica in which he describes his encyclopaedic endeavours as, 'oft-times fain to wander in the America and untravelled parts of Truth'.

At least three 'predictions' in 'A prophecy concerning the future state of several nations' are remarkable -

* 'When Africa shall no more sell out their Blacks/ To make slaves and drudges to the American Tracts'.

* 'When America shall cease to send out its treasure/But employ it at home in American pleasure'.

* 'When the new world shall the old invade/Nor count them their lords but their fellows in trade'.

The 'prophecy' concludes thus-

'Then think strange things are come to light/ Where but few have had a foresight'. [15]

In conclusion, Browne's life-long penchant for utilizing Janus as a symbol is endorsed by the psychologist Carl Gustav Jung who considered Janus to be -

'a perfect symbol of the human psyche, as it faces both the past and future. Anything psychic is Janus-faced: it looks both backwards and forwards. Because it is evolving it is also preparing for the future'. [16]

I've written before about the many ideas shared between Browne and Jung. Not only does one of the earliest recorded usages in modern English of the word 'archetype' occur in Browne's hermetic vision, The Garden of Cyrus but the archetype of 'the wise ruler' itself is sketched through his highly original proper-name symbolism. King Cyrus, Moses, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Solon, Scipio, King Cheops, Hermes Trismegistus and Augustus are all cited in the discourse as exemplary of the archetype of 'the wise ruler'.

Nowadays the phrase 'two-faced' is often a pejorative term, however, from his deep study of the Ancient world to his anticipation of 'future discoveries in Botanical Agriculture', a good case can be made for Thomas Browne to be lauded as the English Janus-faced philosopher. The learned physician's assessment of our own increasingly uncertain times being, 'not like to envy those that shall live in the next, much less three or four hundred Years hence, when no Man can comfortably imagine what Face this World will carry'. [17]

What is certain is that centuries before C.G. Jung, the proto-psychology of Thomas Browne utilized Janus as symbolic of the human psyche. And just like the Roman god Janus, whose name is remembered in the month of January, we too look back to the past and forward to the future in order to define both our times and our individual identity.

Wednesday, October 19, 2022

'In the bed of Cleopatra' - Thomas Browne's Egyptology

Thomas Browne's study of ancient Egypt was multi-faceted; as a doctor he took an interest in its medicine, as a devout Christian he knew that the Biblical books of Genesis and Exodus are set in ancient Egypt; and as a scholar of comparative religion he was familiar with the names and attributes of the Egyptian gods; but above else its from his adherence to Hermetic philosophy that Browne's life-long interest in the Land of the Pharaoh's was sustained. For, in common with almost all alchemists and hermetic philosophers of the 16th and 17th century, Browne believed ancient Egypt to be the birthplace of alchemy and where long lost transmutations of Nature were once performed. And indeed the early civilization skills necessary in baking, brewing and metal-work, as well as cosmetics and perfumery, were all once close guarded secrets. Ancient Egypt was also believed by hermetic philosopher and alchemist alike to be the home of the mythic sage Hermes Trismegistus, inventor of number and hieroglyph and the founding father of all wisdom subsequently passed down in a golden chain of prophets and mystics culminating in Christ.

Just as fans of the pop singer Elvis Presley (1935-77) often collect all kinds of American memorabilia, so too in the 16th and 17th centuries followers of Hermes Trismegistus avidly collected artefacts believed to be of Egyptian origin, and read literature which claimed to be by the Egyptian sage.

Browne's adherence to Hermetic philosophy is writ large in his spiritual testament and psychological self-portrait Religio Medici (1643), the newly-qualified physician declaring - 'The severe schooles shall never laugh me out of the philosophy of Hermes, that this visible world is but a portrait of the invisible.' [1]

Its however more with an eye towards dentistry and with characteristic humour that Browne in the consolatory epistle A Letter to a Friend informs his reader -

'The Egyptian Mummies that I have seen, have had their Mouths open, and somewhat gaping, which affordeth a good opportunity to view and observe their Teeth, wherein 'tis not easie to find any wanting or decayed: and therefore in Egypt, where one Man practised but one Operation, or the Diseases but of single Parts, it must needs be a barren Profession to confine unto that of drawing of Teeth, and little better than to have been Tooth-drawer unto King Pyrrhus, who had but two in his head'.

Browne's knowledge of Egyptian medicine was acquired through reading the Greek historian and traveller Herodotus (c. 484 – c. 425 BCE) whose Histories was the solitary source of information about ancient Egypt for centuries. [2] In Browne's day there was a well-established trade in mummia. Because the skills in Egyptian mummification appeared to preserve the human body for the afterlife in an extraordinary way, the crushed and pulverised parts of Egyptian mummies became popular remedies for all manner of disease and illness. Often mixed or contaminated with bitumen, in reality mummia was of little medicinal value. Thomas Browne for one, deplored its usage in medicine, declaiming in Urn-Burial -

In the foreword to Mysterium Coniunctionis; 'An inquiry into the separation and synthesis of psychic opposites in Alchemy', the seminal psychologist C. G. Jung informs his reader that -

'the "alchemystical" philosophers made the opposites and their union one of the chiefest objects of their work'. [7]

I've written before about how Thomas Browne's diptych Discourses Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus exemplify the Nigredo and Albedo stages of the alchemical opus - of how the two Discourses are opposite each other in respective theme, imagery and truth. The dark and gloomy doubts, fears and speculative uncertainties upon Death featured in Urn-Burial are mirrored by cheerful certainties in the discernment of archetypal patterns in The Garden of Cyrus - of how the two works fulfil the template of basic mandala symbolism with their metaphysical constructs of Time (Urn-Burial) and Space (The Garden of Cyrus) and of the many polarities which they display such as - World/Cosmos, Earth/Sky, Accident/ Design, Decay/Growth, Darkness/Light, Conjecture/Discern, Mortal/Eternal and of course, Grave/Garden.

The concept of polarity (a word Browne is credited with introducing into the English language in its scientific context) is a vital construct of much esoteric schemata. The opposites and their union, as C.G. Jung noted, were a fundamental quest of Hermetic philosopher and alchemist alike. Browne’s literary diptych is, not unlike the human psyche, a complex of opposites or complexio oppositorum (complex of opposites). Unique as a literary diptych, it corresponds to the polarity of the Microcosm-Macrocosm schemata of Hermeticism in which the microcosm little world of man and his mortality, (Urn-Burial) is mirrored by the vast Macrocosm and the Eternal forms or archetypes (The Garden of Cyrus). The polarity of the alchemical maxim solve et coagula (decay and growth) also closely approximates to the diptych's respective themes, as does the diptych's imagery which progresses from darkness and unconsciousness (Urn-Burial) to Light and consciousness (Garden of Cyrus). The previously mentioned alchemical feat of palingenesis, that is, the revivification of a plant from its ashes which the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus (1493-1541) claimed to have performed, shares close semblance too. The funerary ashes of Urn-Burial burst into flower in the botanical delights of The Garden of Cyrus.

C.G. Jung stated that whenever a complex of opposites occur, a unifying symbol, capable of transcending paradox, sometimes emerges. Its far from improbable that Browne found in his study of ancient Egypt two such symbols which he subsequently embedded in his Discourses namely, the Egyptian god Osiris and the Pyramid. As the literary critic Peter Green noted, 'Mystical symbolism is woven throughout the texture of Browne's work and adds, often subconsciously, to its associative power of impact'. [8]

Osiris was one of the most important gods of Ancient Egypt. He plays a double role in Egyptian theology, as both the god of fertility and vegetation and as the embodiment of the dead and resurrected king. Osiris is utilized in Browne's proper-name symbolism in Urn-Burial as an example of how Time devours even the names of the gods themselves - 'Nimrod is lost in Orion, and Osyris in the Dogge-starre'. However, in The Garden of Cyrus the Egyptian god Osiris assumes a more important role, as the god of vegetation and growth who is assisted by his secretary, the great Hermes Trismegistus. In a short paragraph in which the game of Chess, Pyramids, Egyptian gods and astronomy coalesce in an extraordinary stream-of-consciousness association, Browne exclaims -

'In Chesse-boards and Tables we yet finde Pyramids and Squares, I wish we had their true and ancient description, farre different from ours, or the Chet mat of the Persians, and might continue some elegant remarkables, as being an invention as High as Hermes the Secretary of Osyris, figuring the whole world, the motion of the Planets, with Eclipses of Sunne and Moon'.

C.G. Jung noted how Egyptian theology influenced Christianity thus-

See also

On esoterism in 'The Garden of Cyrus'

Carl Jung and Sir Thomas Browne

Paracelsus and Sir Thomas Browne

Books consulted

* Browne: Selected Writings. ed. with an introduction and Index by Kevin Killeen Oxford 2014

* Herodotus : The Histories. Penguin 1954

* Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance Man the Quest for Lost Knowledge

- ed. J. Godwin Thames and Hudson 1979

* C.G. Jung Collected Works Vol. 14 Mysterium Coniunctionis

* 'Egypt' BBC DVD 2005

* 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue of T. Browne and E. Browne's libraries

* Author's 1658 edition of Pseudodoxia Epidemica with Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus

Notes

[1] Religio Medici Part 1:12

[2] Book 2 of Herodotus The Histories includes his observations on Egypt.

[3] 'In his learned Pyramidographia' Browne marg. of 1658 3rd or 4th edition of P. E. Bk 2 chapter 3

[4] R.M. Part 1:34

[5] P.E. Bk 2 ch. 3

[6] Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance Man the Quest for Lost Knowledge J. Godwin. 1979

[7] C. W vol.14 Mysterium Coniunctionis Foreword

[8] Sir Thomas Browne Peter Green -Longmans and Green 1959

[9] C.W. Vol.9 part 1: 229

This one for M. with thanks for encouragement.

Thursday, June 09, 2022

The joy and alchemical play of jigsaws

The earliest jigsaw puzzles were hand-cut from wood and expensive to make, needing skilled workmanship for each individual jigsaw. The 20th century saw the rise of manufactured, mass-produced cardboard puzzles. The popularity of the jigsaw puzzle during the 1930's Depression as an inexpensive form of entertainment can be gauged from the novelist Daphne du Maurier's best-selling gothic love story Rebecca (1938). In du Maurier's fictitious first-person narration, jigsaws are flexible as metaphors, expressive of comprehension and error, along with revealing identity.

In Rebecca Du Maurier's anonymous narrator states-

'What he has told me and all that has happened will tumble into place like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle'.

'The jig-saw pieces came tumbling thick and fast upon me'.

'They were all fitting into place, the jig-saw pieces. The odd strained shapes that I had tried to piece together with my fumbling fingers and they had never fitted'.

'The jig-saw pieces came together piece by piece, and the real Rebecca took shape and form before me'.[1]

Georges Perec (1936-82) was a film maker, essayist and author of the acclaimed novel 'La vie, mode d'emploi' (Life: A user's manual). Jigsaws are integral to the very structure as well as the central story of Perec's novel. Its narrative moves from one room to another, the reader learning about the residents of each room, or its past residents, or about someone they have come into contact with, thus building a picture of an instant in time. La Vie, mode d'emploi is an extraordinary novel, containing painstakingly detailed descriptions and hundreds of individual stories.

The central story of Perec's Post-modern masterpiece concerns itself with the Englishman Bartlebooth who devotes ten years acquiring the skill of painting in water-colours, then ten more years painting every harbour and port he visits while on a world-cruise. Each of Bartlebooth's finished water-colours are methodically dated and posted to a jigsaw maker in Paris. Upon returning to Paris, he devotes the remaining years of his life attempting to complete every jigsaw made from his paintings in precisely the same chronological order of his travels.

In the preamble to La vie mode d'emploi Georges Perec makes a pertinent point about jigsaws, namely, that its how a jigsaw is cut which makes it easy or difficult to complete.

'Contrary to a widely and firmly held belief, it does not matter whether the initial image is easy (or something taken to be easy - a genre scene in the style of Vermeer, for example, or a colour photograph of an Austrian castle) or difficult (a Jackson Pollock, a Pisarro, or the poor paradox of a blank puzzle), its not the subject of the picture, or the painter's technique, which makes a puzzle more or less difficult, but the greater or lesser subtlety of the way it has been cut; and an arbitrary cutting pattern will necessarily produce an arbitrary degree of difficulty, ranging from the extreme of easiness - for edge pieces, patches of light, well-defined objects, lines, transitions -to the tiresome awkwardness of all the other pieces (cloudless skies, sand, meadow, ploughed land, shaded areas etc.) [2]

Its interesting to note that the logo of the world-wide collaborative project known as Wikipedia consists of an incomplete globe made of jigsaw pieces. The incomplete sphere symbolizes the room to add new knowledge as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

Many sub-genres of puzzles exist. Sentimental and kitsch depictions of puppies, kittens, cakes and cottages abound in jigsaw reproductions as well as art-works such as Botticelli's 'Birth of Venus', Monet's 'Poppies' and Bosch's 'Garden of Heavenly Delights'. The primitive artwork style of Charles Wysocki (1928 - 2002) whose work depicts an idealized version of American life of yesteryear and Thomas Kinade (1958 - 2012) a painter of pastoral and idyll scenes with warm, glowing colouration (Gibsons brand) are both well-loved by American jigsaw builders. Puzzles composed purely of brand labels are also popular in America, a long lasting aftereffect of the 1950's when advertising companies gave away free puzzles with their products.

Featuring the comic art-work of Graham Thompson (b. 1940), the so-called Wasgij puzzle (the word 'jigsaw' spelt backwards) challenges the jigsaw builder to have eyes at the back of their head in order to construct a mirror or 'what-happened-next' picture of the action depicted, a far more difficult task than simply referencing a box top picture.

Remembering the trauma of the world-wide health crisis in the past two years its little wonder that comic jigsaws retain their popularity. The prolific Dutch cartoonist Jan van Haasteren (b. Schiedam, Netherlands 1936) has now supplied Jumbo puzzles with over 200 titles. Haasteren's artwork is instantly recognisable, not least for the same characters re-appearing in his puzzles. These include - a crook and tax official, Police Officers, a mother-in-law, Santa Claus, a cat and mouse, an octopus and crab, along with his trade mark, a Shark fin.

In Haasternen's 'Winter Sports' (below) various activities associated with snow and ice are depicted. Its a typically busy, crowded scene of masterful draughtsmanship, reminiscent of a canvas by Breughel.

'the first part was completed when the various components separated out from the chaos of the massa confusa were brought back to unity in the albedo and "all become one". [3]

The dark, initial state which the alchemist called the nigredo stage was also known as the massa confusa or chaos, the not yet differentiated, but capable of differentiation disorder which the adept gradually reduced to order and unity. Hidden and invisible within the chaos of the massa confusa lay the vision of unity which the alchemist aspired to make visible. For the jigsaw builder, contained within the thousand piece heap, which on first sight can arouse despair, there lays invisible within, the vision of a completed jigsaw.

The alchemical discourse The Garden of Cyrus by the English physician-philosopher Sir Thomas Browne (1605-82) has a number of associations to the jigsaw. Long viewed as one of the most difficult puzzles in the entire canon of English literature, most readers of The Garden of Cyrus have struggled and floundered attempting to piece it together, thwarted by the combination of its esoteric theme, dense symbolism and the near breathless haste of its communication. Very few have ever completed Browne's jigsaw puzzle of an essay, yet alone stepped back upon completion to admire the beauty of its hermetic vision.

Composed from numerous 'stand-alone' notebook jottings, not unlike solitary pieces of a puzzle, Browne cites evidence of the inter-related symbols of Quincunx pattern, number 5 and letter X in topics equal in diversity as jigsaw subject-matter, including- Biblical scholarship, Egyptology, comparative religion, mythology, ancient world plantations, gardening, generation, geometry, germination, heredity, the Archimedean solids, sculpture, numismatics, architecture, paving-stones, battle-formations, optics, zoology, ornithology, the kabbalah, astrology and astronomy, in order to prove to his reader the interconnectivity of all life. Predominate themes of the discourse include - Order, Number, Design and Pattern, all of which are related to jigsaws.

Fascinated by all manner of puzzle throughout his life, whether hieroglyph, riddle, anagram or mystery in nature, Browne in The Garden of Cyrus connects the quincunx pattern found in mineral crystals in the earth below to star constellations in the heavens above; thus a primary objective of his discourse ultimately is none other than advocation of intelligent design. In Browne's hermetic vision, the cosmos itself is a fully interlocking jigsaw, designed through the 'higher mathematics' of the 'supreme Geometrician' i.e. God.

If anything however, its perhaps more the art and design of the jigsaw cutter which Browne celebrates. He's credited by the Oxford Dictionary as the first writer to use the word 'Network' in an artificial context in the English language, (in the full running title of the discourse, The Garden of Cyrus, or the Quincuncial Lozenge, or Network Plantations of the ancients, artificially, naturally, mystically considered). The frontispiece to Browne's discourse resembles some kind of grid cutter for an unusual jigsaw or a gaming board for Go or Backgammon.

Its Latin quotation reads -'What is more beautiful than the Quincunx, which, however you view it, presents straight lines'.

One particular jigsaw shape of interest to Browne in his quinary quest is the so-called 'dancing man' or 'T-man' piece with its 4 + 1 structure (below left). Its a reduced form of ' Square man' by the Roman architect Vitruvius of the human form as drawn by the Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci in his Vitruvian man (below, right) which is alluded to in The Garden of Cyrus thus -

'Nor is the same observable only in some parts, but in the whole body of man, which upon the extension of arms and legs, doth make out a square whose intersection is at the genitals. To omit the phantastical Quincunx in Plato of the first Hermaphrodite or double man, united at the Loynes, which Jupiter divided. [4]

Photos

Top - Wooden 60 piece puzzle of elephant. Wentworth. Completed January 2022

'Bavaria' Ryba, 2000 pieces Heye. Completed July 2022

Dolomite Mountains, Italy, Trefl 500 pieces, Completed March 2022

Norfolk Windmill and river Falcon 500 pieces. Completed Feb. 2021.

Winter Sports by Jan van Haasteren Jumbo 1000 pieces. Completed February 2022

'I Love Spring' by Mike Jupp Gibsons 1000 pieces. Completed May 2022

'Apocalypse 2000' by Jean Jacques Loup Falcon 1000 pieces. Completed June 2022

Colour Wheel. 1000 pieces. Made in China. Completed September 2022

The Table of the Muses. USA Springbok 1968. Completed November 2022

N.B. The Wikipedia entry on puzzles has numerous links to articles about jigsaws.

Notes

[1] Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier First published by Victor Gollancz 1938 chapter 20.

[2] George Perec La vie mode d'emploi First published in France in 1978 by Hachette/ Collection P.O.L. Paris and in Great Britain in 1987 by Collins Harvill

[3] C.G. Jung Collected Works Vol 14. Mysterium Coniunctionis An enquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of psychic opposites in alchemy translated by R. F. C. Hull 1963 paragraph 388

[4] Thomas Browne : Selected Writings edited by Kevin Killeen Oxford University Press 2014 . Quote from chapter 3 of The Garden of Cyrus

[5] An unpublished footnote from a source equal in veracity to Fragment on Mummies.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)

.jpg)

_blu.svg.png)