Often defined as a polymath because of the multiplicity of his interests, scientific, antiquarian and esoteric, an equally useful and perhaps preciser definition of the philosopher-physician Thomas Browne (1605-82) is that of early or proto-psychologist.

As a doctor practising in the 17th century Browne had plenty of occasion to observe mental trauma through endemic sickness, disease and bereavement. Living through one of the most psychologically disturbed times in English history he also witnessed extremes of human behaviour during the Civil war and its consequences.

In essence the four primary elements of Browne's proto-psychology are - his capacity for self-analysis and lifelong interest in people, usage of proper-noun symbolism and a fascination with the inner world of dreams. Furthermore, modern scholarship has recently detected that there is a remarkable relationship between Browne's proto-psychology to Carl Jung's analytical psychology.

Officially published in 1643 Browne's Religio Medici remains a classic of World literature; its thought-provoking soliloquies reward the attention of casual reader and academic alike.

The first ever comparative edition of Religio Medici was published by Oxford University Press in April 2023 after protracted delay. Edited by Reid Barbour and Brooke Conti, the scholarly introduction to the Oxford edition of Browne's Collected Works discusses Religio Medici's major themes and reception, citing the Romantic poet Coleridge, who proposed it should be read 'in a dramatic & not in a metaphysical View - as a sweet Exhibition of character & passion & not as an Expression or Investigation of positive Truth'. [1]

The first volume of the ambitious project to publish a critical edition of the Thomas Browne's complete works reproduces three different versions of his Religio Medici (1643) for the first time. The Pembroke manuscript, a subsequent revised version and the official version are all reproduced, making it easier to identify text which Browne subsequently excluded from the authorized version. Only the early Pembroke version includes the following text, declared in a typical fusion of spirituality, scientific enquiry and hermetic imagery-

'Those strange and mystical transmigrations that I have observed in silkworms, turned my Philosophy into Divinity...............I have therefore forsaken those strict definitions of Death, by privation of life, extinction of natural heat, separation &c. of soul and body, and have framed one in hermetical way unto my own fancy - death is the final change, by which that noble portion of the microcosm is perfected (Latin trans.) for to me that considers things in a natural or experimental way, man seems to be but a digestion or a preparative way unto the last and glorious Elixir which lies imprisoned in the chains of flesh'. [2]

The first readers of Religio Medici were at turns shocked, astonished and admiring of Browne's frank display of his enigmatic personality and his advocacy for greater tolerance in religious belief. He also invites his reader to witness the labyrinthine meanderings of his thought and a precocious talent for self-analysis is prominent throughout its pages.

In many ways self-examination and self understanding is the bedrock foundation of Browne's proto-psychology; without such rigours he'd never achieved individuation or developed fully in creativity.

In Religio Medici the newly-qualified physician informs his reader of the psychic crisis he'd experienced during his trial of self-examination. His devout Christian faith was of its time, Hell along with the Devil were very real psychic entities to him.

'The heart of man is the place the devil dwells in. I feel sometimes a hell within myself, Lucifer keeps

his court in my breast, Legion is revived in me'. [3]

'Tis that unruly regiment within me that will destroy me, 'tis I that do infect myself, the man without a Navel yet lives in me; I feel that original canker corrode and devour me. Lord deliver me from myself'.[4]

'The Devil that did but buffet Saint Paul, plays me thinks at Sharp with me. Let me be nothing if within the compass of my self, I do not find the battle of Lepanto passion against reason, reason against faith, faith against the Devil, and my conscience against all..There is another man within me that's angry with me, rebukes, commands and eastwards me'. [ 5]

'Thus did the devil did play Chess with me and yielding a pawn thought to gain a Queen from me. And whilst I laboured to raise the structure of my reason he strove to undermine the edifice of my faith'. [6]

*

Its testimony to his lifelong interest in people that even when he was advanced in years, when asked for his medical advice, Browne dutifully made the journey from his home in Norwich to the sea-port of Yarmouth. He recorded his doctor's call and very early case-history on the eating disorder known as bulimia in his commonplace notebook thus-

'There is a woman now Living in Yarmouth named Elizabeth Michell, an hundred and two years old, a person of 4 foot and an half high, very lean, very poor, and Living in a meane room without ordinary accommodation. Her youngest son is 45 years old; though she answers well enough to ordinary Questions, yet she conceives her eldest daughter to be her mother. Butt what is remarkable in her is a kind of boulime or dog appetite; she greedily eating day and night all that her allowance, friends and charitable people afford her, drinking beer or water, and making little distinction of any food either of broths, flesh, fish, apples, pears, and any coarse food in no small quantity, insomuch that the overseers of late have been fain to augment her weekly allowance. She sleeps indifferently well till hunger awakes her and then she must have no ordinary supply whether in the day or night. She vomits not, nor is very laxative. This is the oldest example of the sal esurinum chymicorum, which I have taken notice of; though I am ready to afford my charity unto her, yet I should be loth to spend a piece of ambergris I have upon her, and to allow six grains to every dose till I found some effect in moderating her appetite: though that be esteemed a great specific in her condition'. [7]

*

Symbols are integral to Browne's proto-psychology. In Religio Medici Egyptian hieroglyphs along with the 'book of nature' and music are each proposed to contain symbols which provide a wealth of spiritual wisdom to the receptive enquirer. The sources of Browne's literary symbolism are varied. The Bible and Greek mythology were rich hunting grounds for his proper-name symbolism. He also developed 'home-grown' symbols such as the urn and quincunx which enable him, 'by concentrating, almost like a hypnotist, on this pair of unfamiliar symbols, to paradoxically release the reader's mind into an infinite number of associative levels of awareness, without preconception to give shape and substance to quite literally cosmic generalizations'. [8]

Geographic place names and their frequently unconscious associations are also utilized by Browne. One in particular made a big impression upon C.G. Jung. It was the South African traveller and explorer Laurens van der Post (1906-96) who introduced Carl Jung to one of the greatest of all Browne's psychological observations which celebrates the mystery of consciousness and employs a highly original proper-place name symbol fitting of the unconscious psyche. Van der Post quoted Browne’s bold declaration -

'We carry within us the wonders we seek without us. There is all Africa, and her prodigies in us';

and recorded Jung's response. ‘He was deeply moved. He wrote it down and exclaimed 'that was, and is, just it. But it needed the Africa without to drive home the point in my own self'. Clearly, Jung was impressed by Browne's proto-psychology proper-name symbolism. [9]

It remains unknown whether Jung read Religio Medici which was translated into German in 1746. Jung was however fond of quoting its title and once stated – ‘For the educated person who studied alchemy as part of his general education it was a real Religio medici [10]

According to Jung the seventeenth century was the era in which alchemy and hermetic philosophy attained their most significance. In his view Browne’s era was 'one of those periods in human history when symbol formation still went on unimpeded'. He also noted that Hermetic philosophy was, in the main, practised by physicians not only because many known alchemists were physicians, but also because chemistry in those days was essentially a pharmacopeia. [11]

Jung's psychology is based upon the protean multiplicity of symbols which the human psyche ceaselessly creates. The symbolic meaning of almost every ancient world myth, animal, geometric form, feature of Nature, planetary god and number is elaborated upon in his writings, for he believed that-

'The protean mythologeme and the shimmering symbol express the processes of the psyche far more trenchantly and, in the end, far more clearly than the clearest concept; for the symbol not only conveys a visualization of the process but—and this is perhaps just as important—it also brings a re-experiencing it'. [13]

The Roman god Janus is a superb example of how Browne’s proto-psychology anticipates Jung's interpretation of symbols . The double-faced god Janus who presents his two faces simultaneously to the past and future appears as a proper-name symbol in each of Browne’s literary works. In Urn-Burial the gloomy but realistic thought that, 'one face of Janus holds no proportion to the other' occurs, while in Cyrus the finger language of 'the mystical statua of Janus' is featured. The double-faced god clearly held proto-psychological significance to Browne. Centuries later, Carl Jung declared the Roman god Janus to be none other than, 'a perfect symbol of the human psyche, as it faces both the past and future. Anything psychic is Janus-faced: it looks both backwards and forwards. Because it is evolving it is also preparing for the future'. [14]

Listed as once in Browne's library, the five gargantuan tomes of the Theatrum Chemicum were the most popular and comprehensive collection of alchemical literature available in the seventeenth century. A woodcut depicting the Nigredo stage of alchemy is reproduced in its first volume. (above). Encased within a bubble the researcher lays prone with a black crow on his stomach. The five planets and two luminaries orbit above him. The black star of Saturn, a planet long associated with melancholy and isolation as well as deep insight, radiates its dark influence upon the researcher.

We can be confident Browne perused his edition of the Theatrum Chemicun closely for he 'borrowed' from the Belgian alchemist Gerard Dorn (c. 1530-84) whose highly moral and psychological writings form the bulk of its first volume the image of an 'invisible sun'. Browne's 'borrowing' from Dorn occurs in the fifth and final chapter of Urn-Burial where he inspirationally declares - 'Life is a pure flame, and we live by an invisible sun within us'.

Although he lacked modern-day terminology Browne nonetheless was adept in his usage of symbols and imagery to describe the workings of the psyche. He was well acquainted through his reading of alchemical literature such as the Theatrum Chemicum with the sophisticated, yet commonplace schemata of the alchemical stages of the opus known as the Nigredo (Blackness) and Albedo (Whiteness). There's strong evidence that this concept is utilized as the framework for his Discourses. A superabundance of similarities can be discerned, far beyond casual coincidence, between the themes, imagery and symbols of Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus to those of the Nigredo and Albedo of alchemy.

C.G. Jung helpfully defines the initial nigredo stage of alchemy thus-

'the nigredo not only brought decay, suffering, death, and the torments of hell visibly before the eyes of the alchemist, it also cast the shadow of melancholy over his solitary soul. In the blackness of his despair he experienced.. grotesque images which reflect the conflict of opposites into which the researcher's curiosity had led him. His work began with a katabasis, a journey to the underworld as Dante also experienced it'. [15]

Urn-Burial alludes to several 'soul journeys' of classical literature, including Dante's Inferno as well as Homer's Odyssey in which Ulysses descends into the Underworld. the Discourse also alludes to the soul journeys of Scipio's Dream and Plato's myth of Er. The religious mystic in Browne knew that each one of us from our birth, conscious or not of the fact, embarks upon a soul-journey with Death as a final port of call.

Alchemical literature frequently warns the researcher of the dangers of being engulfed and overwhelmed by the dark contents of the initial stage of the nigredo. Browne resisted this peril through professional acumen, but was also aware of how other's succumbed to the despair of the Nigredo -

'It is the heaviest stone that melancholy can throw at a man, to tell him he is at the end of his nature; or that there is no further state to come, unto which this seems progressional, and otherwise made in vain. [16]

Browne’s proto-psychology in Urn-Burial stoically notes of the relationship between pain and memory.

‘We slightly remember our felicities, and the smartest strokes of affliction leave but short smart upon us. Sense endureth no extremities, and sorrows destroy us or themselves. … To be ignorant of evils to come, and forgetful of evils past, is a merciful provision in nature.' [17]

The Nigredo is encapsulated perfectly in Urn-Burial's pithy expression, 'lost in the uncomfortable night of nothing'. Though little recognised, Browne's forensic survey of the burial rites and customs of various world religions, contemplation of ancient world beliefs associated with death and the afterlife along with its mention of putrefaction and mortification makes it the most sustained and exemplary work of the Nigredo stage of alchemy extant in English literature.

The succeeding stage of the alchemical opus was known as the albedo or whitening in which a widening of consciousness and revelation occurs. The albedo is frequently likened in alchemical literature to the Creation, Paradise and the Garden of Eden, each of which are alluded to in the opening paragraphs of The Garden of Cyrus.

Misapprehension and prejudice continues to bedevil understanding of the vital influence which alchemy, Neoplatonic thought and Hermetic philosophy exerted upon artist, scientist and philosopher alike throughout the Renaissance. Such misapprehensions continue to hamper comprehension of Browne who read and studied alchemical literature closely, as the contents of his library reveals. Along with other spiritual alchemists Browne intuited the bizarre symbolism and imagery of alchemy as a proto-psychology which discoursed upon the unconscious processes of the psyche to attain self-knowledge and individuation, the very Philosopher's Stone no less. In essence, Browne recognised in alchemical literature a kinship to the moralism and insights of Christian theology. Spiritually orientated alchemy is his greatest interest, as he makes clear in Religio Medici -

'The smattering I have of the Philosopher's Stone (which is something more than the perfect exaltation of gold) hath taught me a great deal of theology'. [18]

Even late in his life, when orthodox in his Christian faith, Browne justified the study of esoteric literature, naming two mystical scientists he held in high regard in Christian Morals - 'many would be content that some would write like Helmont and Paracelsus; and be willing to endure the monstrosity of some opinions, for divers singular notions requiting such aberrations'. [19]

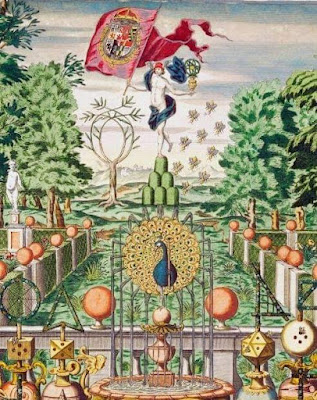

The frontispiece to Mario Bettini's Beehives of Univeral Mathematical Philosophy (published in 1656 and listed as once in Browne's library) is a fitting visualization of the overall mood-music of The Garden of Cyrus. In its foreground is a villa courtyard in which mathematical, optical and geometric instruments stand in vases as if cultivated plants. In the centre of the courtyard a peacock stands upon a sphere and displays its feathers, water flows from its feathered eyes creating a streaming fountain. Mercurius, the god of communication and revelation stands aloft a pyramid of skep beehives holding an armillary sphere. Ten bees in quincunx formation hover beside him.

The Garden of Cyrus is crowded with concepts and symbols from various Western esoteric disciplines. The quincunx is one of many symbols featured in the discourse. Although the quincunx is mentioned in classical antiquity the idea of it being a pattern which transcends the realm of the artificial originates from the Renaissance. The idea can be found in book 4 of the Italian polymath and scholar Giambattista Della Porta's vast agricultural encyclopedia known as Villa (1583-1592). Della Porta (1535-1615) asserts in Villa that the quincunx pattern in addition to featuring in gardens and plantations, 'is to be found in each and every single thing in nature'. An illustration of the quincunx pattern from Della Porta's Villa was borrowed by Browne for the frontispiece of The Garden of Cyrus. Astoundingly, centuries later, C.G. Jung declared the quincunx to be none other than 'a symbol of the quinta essentia which is identical to the Philosopher's Stone'. [20]

In contrast to Urn-Burial's slow, stately rhythms, The Garden of Cyrus includes many paragraphs of rapid, near breathless prose. In a rare first person outburst Browne couples the game of chess to Persia to Egyptian deities, Hermes Trismegistus to cosmology to the potent alchemical 'coniunctio' symbol of Sol et Luna in a train of stream-of-consciousness association.

'In Chess-boards and Tables we yet find Pyramids and Squares, I wish we had their true and ancient description, far different from ours, or the Chet mat of the Persians, which might continue some elegant remarkables, as being an invention as High as Hermes the Secretary of Osyris, figuring the whole world, the motion of the Planets, with Eclipses of Sun and Moon'. [21]

While Urn-Burial with its oratorical flourishes and 'full Organ-stop' prose exhibits distinctly baroque traits thematically and stylistically, in complete contrast The Garden of Cyrus has strong Mannerist characteristics in style and theme. The Hungarian art-historian Arnold Hauser noted that Mannerist art delighted in symbols and hidden meanings and that it had an intellectual and even surrealistic outlook. He also noted that Mannerist art was inclined towards esoteric concepts and defined its qualities and excesses in words easily applicable to Browne's creativity and the hermetic content of The Garden of Cyrus.

'At one time it is the deepening and spiritualizing of religious experience and a vision of a new spiritual content in life; at another, an exaggerated intellectualism, consciously and deliberately deforming reality, with a tinge of the bizarre and the abstruse.' [22]

C.G. Jung studied and borrowed from hermetic philosopher and alchemist alike in the development of his psychology. His great achievement was identifying the unconscious imagery of the alchemists to be a proto-psychology which discusses the stages and processes of the psyche in its striving towards Self-realization and individuation. Foremost of all symbols in Jung's psychology are the archetypes, the primordial models of the psyche which he believed are embedded at the deepest strata of the collective psyche; some of the most important are the hero, the lover, the Great Mother, the wise ruler and the trickster.

Although mention of archetypes can be traced back to Plato and Gnostic philosophers, one of the earliest modern usages of the word 'archetype' occurs in The Garden of Cyrus. Browne even attempts to delineate a specific archetype, that of the 'wise ruler' through proper-name symbolism allusion to the Persian King Cyrus, the biblical leaders Solomon and Moses, the Roman Emperor Augustus and the Macedonian Alexander the Great. The archetype of the 'Great Mother' is also tentatively sketched in Cyrus through allusion to the matriarchal figures of Sarah of the Hebrew Old Testament, the Greek goddess Juno, and Isis of ancient Egypt.

Another great example of how Browne's proto-psychology anticipates Jung's occurs at the apotheosis of The Garden of Cyrus with his advising his reader 'to search out the quaternio's and figured draughts of this order'. Its advice was taken seriously by Carl Jung with the Swiss psychoanalyst firmly believing that the quaternity or patterns which are four-fold to invariably symbolize wholeness or totality; and in fact the earliest known divisions of Space and Time - the four seasons of the Year and the four points of the compass are based upon a quaternity, as are the four humours of ancient Greek medicine along with the four temperaments of medieval medicine as well as the four gospels of the New Testament. Jung even structured his understanding of the psyche upon a quaternity, defining the psyche as comprising of four entities in totality, these being - Rational thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition.

*

C.G. Jung once declared - 'the late alchemical texts are fantastic and baroque; only when we have learnt to interpret them can we recognise what treasures they hide'. [23] Today Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus (1658) can be identified as Browne's supreme work of proto-psychology. Jam-packed with symbolism and imagery allusive to esoteric concepts, together they form a portrait of the psyche, unconscious and conscious, irrational and rational, stoical and transcendent, fearful of Death yet always planning for the future.

Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus are highly polarised to each other in respective truth, imagery and symbolism. The invisible world of decay and death in Urn-Burial is 'answered' by the visible world of growth and life in The Garden of Cyrus. Imagery of darkness in Urn-Burial is mirrored by imagery of Light in The Garden of Cyrus. Likewise, the gloomy, Saturnine speculations of Urn-Burial are 'answered' by the cheerful, Mercurial revelations of Cyrus. Together the diptych traces a commonplace route of 'Soul-journey' literature from the Grave to the Garden. Browne’s soul-journey begins in the ‘subterranean world’ of Urn-Burial's opening paragraph and arrives at ‘the City of Heaven’ in the penultimate paragraph of Cyrus. The gordian knot of why these two philosophical discourses of 1658 share a multiplicity of oppositions or polarities thematically and in imagery such as - Darkness and Light, Decay and Growth, Mortality and Eternity, Body and Soul, Accident and Design, Speculation and Revelation, World and Universe, Microcosm and Macrocosm is swiftly spliced by C. G. Jung's sharp remark - 'the alchemystical philosophers made the opposites and their union their chiefest concern'. [24]

*

The altered state of

consciousness known as dreaming fascinated Browne. It remains unknown why exactly we dream. For most dreams are involuntary, a sequence of strange events and unfamiliar

places which are out of one’s control and which simply happen to one when asleep.

Browne however was one of those fortunate people able to manipulate the

sequence of events of a dream at will, so-called lucid dreaming. Supplementing his many observations on dreams in Religio Medici Browne describes his

ability to lucid dream thus-

'Yet in one dream I can compose a

whole comedy, behold the action, apprehend the jests and laugh myself awake at

the conceits thereof. Were my memory as faithful as my reason is fruitful I

would chose never to study but in my dreams'. [25]

For those living in the grim realities of the seventeenth century, the ability to lucid dream must have been a welcome diversion. In tandem with his wide-ranging reading lucid dreaming was rich fuel for Browne’s artistic imagination.

Concrete evidence of the relationship between Browne’s proto-psychology to modern-day psychoanalysis can be found in his short tract on dreams. Taking his cue from Paracelsus on the psychotherapeutic value of interpreting dreams, especially at a critical stage of a patient’s illness, Browne expounds his theory for interpreting dreams thus-

'Many dreams are made out by

sagacious exposition and from the signature of their subjects; carrying their

interpretation in their fundamental sense and mystery of similitude

whereby he that understands upon what natural fundamental every notional dependeth, may by symbolical adaption hold a ready way to read the characters of

Morpheus'. [26]

Browne's proposal that dreams can be interpreted by 'symbolical adaptation' links him closely to Jung's psychology for the Swiss analyst also believed that his patients dreams could be interpreted through 'symbolical adaptation'.

Browne states in his tract that dreams have changed lives, naming J.B. van Helmont and Jerome Cardan as recipients of transformative dreams. Centuries later, after dreaming of being trapped in the 17th century, Jung embarked upon what was to be over thirty years study of alchemy and its literature.

Conclusion

Writing in 1961 the American psychiatrist Jerome Schneck asserted- 'When Browne is assessed with the context of modern medico-psychological principles, the strength and richness of his thoughts and the appreciation of him as a psychologically minded physician comes to more fruitful expression. It may be reasonable to predict that more elements of interest in Sir Thomas Browne will be discovered in the future. He will find a more significant place in psychiatry. His importance in the history of medicine will be more fully perceived'. [27]

Browne is far more interested in the Renaissance discovery of the psyche than the discoveries of the two scientific instruments which advanced and developed scientific understanding in his lifetime, the telescope and microscope. This is because, above all, it is spirituality and processes of the mind, in particular self-realization and individuation which are of primary interest to him. Browne's only science of value today is his contribution to the science of the mind. He would doubtless have agreed with Carl Jung’s assessment of our modern-day world.

‘Science and technology have indeed conquered the world, but whether the psyche has gained anything is another matter’. [28]

Today, Sir Thomas Browne can confidently be termed an early or proto-psychologist. His capacity for self-analysis, deep interest in people, usage of symbolism and fascination with dreams are each vital components of his proto psychology. Though lacking in terminology, he nonetheless attempted through his proper-name symbolism and imagery such as 'the theatre of ourselves' to discourse upon the psyche. But perhaps his greatest achievement as a proto psychologist is simply his introduction into English language words useful to his profession such as - ‘medical’ ‘pathology’ 'suicide' ‘hallucination’ and best of all ‘therapeutic’. Furthermore, as I hope I've adequately proved, Thomas Browne’s proto-psychology has a unique, and yet to be fully explored relationship to the analytical psychology of Carl Jung.