Friday, February 24, 2023

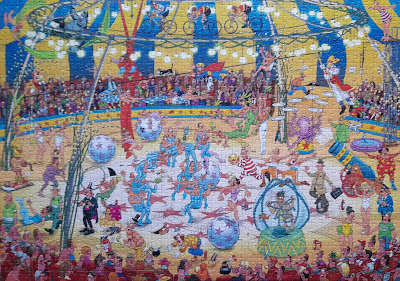

The comic genius of Jan van Haasternen

Thursday, June 09, 2022

The joy and alchemical play of jigsaws

The earliest jigsaw puzzles were hand-cut from wood and expensive to make, needing skilled workmanship for each individual jigsaw. The 20th century saw the rise of manufactured, mass-produced cardboard puzzles. The popularity of the jigsaw puzzle during the 1930's Depression as an inexpensive form of entertainment can be gauged from the novelist Daphne du Maurier's best-selling gothic love story Rebecca (1938). In du Maurier's fictitious first-person narration, jigsaws are flexible as metaphors, expressive of comprehension and error, along with revealing identity.

In Rebecca Du Maurier's anonymous narrator states-

'What he has told me and all that has happened will tumble into place like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle'.

'The jig-saw pieces came tumbling thick and fast upon me'.

'They were all fitting into place, the jig-saw pieces. The odd strained shapes that I had tried to piece together with my fumbling fingers and they had never fitted'.

'The jig-saw pieces came together piece by piece, and the real Rebecca took shape and form before me'.[1]

Georges Perec (1936-82) was a film maker, essayist and author of the acclaimed novel 'La vie, mode d'emploi' (Life: A user's manual). Jigsaws are integral to the very structure as well as the central story of Perec's novel. Its narrative moves from one room to another, the reader learning about the residents of each room, or its past residents, or about someone they have come into contact with, thus building a picture of an instant in time. La Vie, mode d'emploi is an extraordinary novel, containing painstakingly detailed descriptions and hundreds of individual stories.

The central story of Perec's Post-modern masterpiece concerns itself with the Englishman Bartlebooth who devotes ten years acquiring the skill of painting in water-colours, then ten more years painting every harbour and port he visits while on a world-cruise. Each of Bartlebooth's finished water-colours are methodically dated and posted to a jigsaw maker in Paris. Upon returning to Paris, he devotes the remaining years of his life attempting to complete every jigsaw made from his paintings in precisely the same chronological order of his travels.

In the preamble to La vie mode d'emploi Georges Perec makes a pertinent point about jigsaws, namely, that its how a jigsaw is cut which makes it easy or difficult to complete.

'Contrary to a widely and firmly held belief, it does not matter whether the initial image is easy (or something taken to be easy - a genre scene in the style of Vermeer, for example, or a colour photograph of an Austrian castle) or difficult (a Jackson Pollock, a Pisarro, or the poor paradox of a blank puzzle), its not the subject of the picture, or the painter's technique, which makes a puzzle more or less difficult, but the greater or lesser subtlety of the way it has been cut; and an arbitrary cutting pattern will necessarily produce an arbitrary degree of difficulty, ranging from the extreme of easiness - for edge pieces, patches of light, well-defined objects, lines, transitions -to the tiresome awkwardness of all the other pieces (cloudless skies, sand, meadow, ploughed land, shaded areas etc.) [2]

Its interesting to note that the logo of the world-wide collaborative project known as Wikipedia consists of an incomplete globe made of jigsaw pieces. The incomplete sphere symbolizes the room to add new knowledge as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle.

Many sub-genres of puzzles exist. Sentimental and kitsch depictions of puppies, kittens, cakes and cottages abound in jigsaw reproductions as well as art-works such as Botticelli's 'Birth of Venus', Monet's 'Poppies' and Bosch's 'Garden of Heavenly Delights'. The primitive artwork style of Charles Wysocki (1928 - 2002) whose work depicts an idealized version of American life of yesteryear and Thomas Kinade (1958 - 2012) a painter of pastoral and idyll scenes with warm, glowing colouration (Gibsons brand) are both well-loved by American jigsaw builders. Puzzles composed purely of brand labels are also popular in America, a long lasting aftereffect of the 1950's when advertising companies gave away free puzzles with their products.

Featuring the comic art-work of Graham Thompson (b. 1940), the so-called Wasgij puzzle (the word 'jigsaw' spelt backwards) challenges the jigsaw builder to have eyes at the back of their head in order to construct a mirror or 'what-happened-next' picture of the action depicted, a far more difficult task than simply referencing a box top picture.

Remembering the trauma of the world-wide health crisis in the past two years its little wonder that comic jigsaws retain their popularity. The prolific Dutch cartoonist Jan van Haasteren (b. Schiedam, Netherlands 1936) has now supplied Jumbo puzzles with over 200 titles. Haasteren's artwork is instantly recognisable, not least for the same characters re-appearing in his puzzles. These include - a crook and tax official, Police Officers, a mother-in-law, Santa Claus, a cat and mouse, an octopus and crab, along with his trade mark, a Shark fin.

In Haasternen's 'Winter Sports' (below) various activities associated with snow and ice are depicted. Its a typically busy, crowded scene of masterful draughtsmanship, reminiscent of a canvas by Breughel.

'the first part was completed when the various components separated out from the chaos of the massa confusa were brought back to unity in the albedo and "all become one". [3]

The dark, initial state which the alchemist called the nigredo stage was also known as the massa confusa or chaos, the not yet differentiated, but capable of differentiation disorder which the adept gradually reduced to order and unity. Hidden and invisible within the chaos of the massa confusa lay the vision of unity which the alchemist aspired to make visible. For the jigsaw builder, contained within the thousand piece heap, which on first sight can arouse despair, there lays invisible within, the vision of a completed jigsaw.

The alchemical discourse The Garden of Cyrus by the English physician-philosopher Sir Thomas Browne (1605-82) has a number of associations to the jigsaw. Long viewed as one of the most difficult puzzles in the entire canon of English literature, most readers of The Garden of Cyrus have struggled and floundered attempting to piece it together, thwarted by the combination of its esoteric theme, dense symbolism and the near breathless haste of its communication. Very few have ever completed Browne's jigsaw puzzle of an essay, yet alone stepped back upon completion to admire the beauty of its hermetic vision.

Composed from numerous 'stand-alone' notebook jottings, not unlike solitary pieces of a puzzle, Browne cites evidence of the inter-related symbols of Quincunx pattern, number 5 and letter X in topics equal in diversity as jigsaw subject-matter, including- Biblical scholarship, Egyptology, comparative religion, mythology, ancient world plantations, gardening, generation, geometry, germination, heredity, the Archimedean solids, sculpture, numismatics, architecture, paving-stones, battle-formations, optics, zoology, ornithology, the kabbalah, astrology and astronomy, in order to prove to his reader the interconnectivity of all life. Predominate themes of the discourse include - Order, Number, Design and Pattern, all of which are related to jigsaws.

Fascinated by all manner of puzzle throughout his life, whether hieroglyph, riddle, anagram or mystery in nature, Browne in The Garden of Cyrus connects the quincunx pattern found in mineral crystals in the earth below to star constellations in the heavens above; thus a primary objective of his discourse ultimately is none other than advocation of intelligent design. In Browne's hermetic vision, the cosmos itself is a fully interlocking jigsaw, designed through the 'higher mathematics' of the 'supreme Geometrician' i.e. God.

If anything however, its perhaps more the art and design of the jigsaw cutter which Browne celebrates. He's credited by the Oxford Dictionary as the first writer to use the word 'Network' in an artificial context in the English language, (in the full running title of the discourse, The Garden of Cyrus, or the Quincuncial Lozenge, or Network Plantations of the ancients, artificially, naturally, mystically considered). The frontispiece to Browne's discourse resembles some kind of grid cutter for an unusual jigsaw or a gaming board for Go or Backgammon.

Its Latin quotation reads -'What is more beautiful than the Quincunx, which, however you view it, presents straight lines'.

One particular jigsaw shape of interest to Browne in his quinary quest is the so-called 'dancing man' or 'T-man' piece with its 4 + 1 structure (below left). Its a reduced form of ' Square man' by the Roman architect Vitruvius of the human form as drawn by the Renaissance polymath Leonardo da Vinci in his Vitruvian man (below, right) which is alluded to in The Garden of Cyrus thus -

'Nor is the same observable only in some parts, but in the whole body of man, which upon the extension of arms and legs, doth make out a square whose intersection is at the genitals. To omit the phantastical Quincunx in Plato of the first Hermaphrodite or double man, united at the Loynes, which Jupiter divided. [4]

Photos

Top - Wooden 60 piece puzzle of elephant. Wentworth. Completed January 2022

'Bavaria' Ryba, 2000 pieces Heye. Completed July 2022

Dolomite Mountains, Italy, Trefl 500 pieces, Completed March 2022

Norfolk Windmill and river Falcon 500 pieces. Completed Feb. 2021.

Winter Sports by Jan van Haasteren Jumbo 1000 pieces. Completed February 2022

'I Love Spring' by Mike Jupp Gibsons 1000 pieces. Completed May 2022

'Apocalypse 2000' by Jean Jacques Loup Falcon 1000 pieces. Completed June 2022

Colour Wheel. 1000 pieces. Made in China. Completed September 2022

The Table of the Muses. USA Springbok 1968. Completed November 2022

N.B. The Wikipedia entry on puzzles has numerous links to articles about jigsaws.

Notes

[1] Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier First published by Victor Gollancz 1938 chapter 20.

[2] George Perec La vie mode d'emploi First published in France in 1978 by Hachette/ Collection P.O.L. Paris and in Great Britain in 1987 by Collins Harvill

[3] C.G. Jung Collected Works Vol 14. Mysterium Coniunctionis An enquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of psychic opposites in alchemy translated by R. F. C. Hull 1963 paragraph 388

[4] Thomas Browne : Selected Writings edited by Kevin Killeen Oxford University Press 2014 . Quote from chapter 3 of The Garden of Cyrus

[5] An unpublished footnote from a source equal in veracity to Fragment on Mummies.

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg)