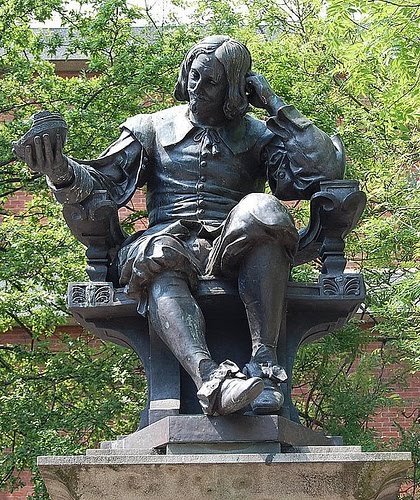

There are a surprising number of hitherto

undetected connections between the German mathematician, astronomer, and

astrologer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) to the English physician and

philosopher Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682).

Kepler’s life, like Browne’s, spanned

a watershed in scientific thought. Kepler not only advocated rational

inductive science and the astronomical discoveries of Galileo but also augmented

his scientific enquiries with Neoplatonic and Pythagorean ideas. Kepler’s

astronomical discoveries were as much structured upon precise mathematical

calculation as deeply held theological beliefs and God-given revelation; his scientific perspective, not unlike Browne’s own scientific perspective a

full half century later, were an admixture of Christian awe of the Creation, precise mathematical analysis and Platonic and Pythagorean concepts of the ancient Greek world.

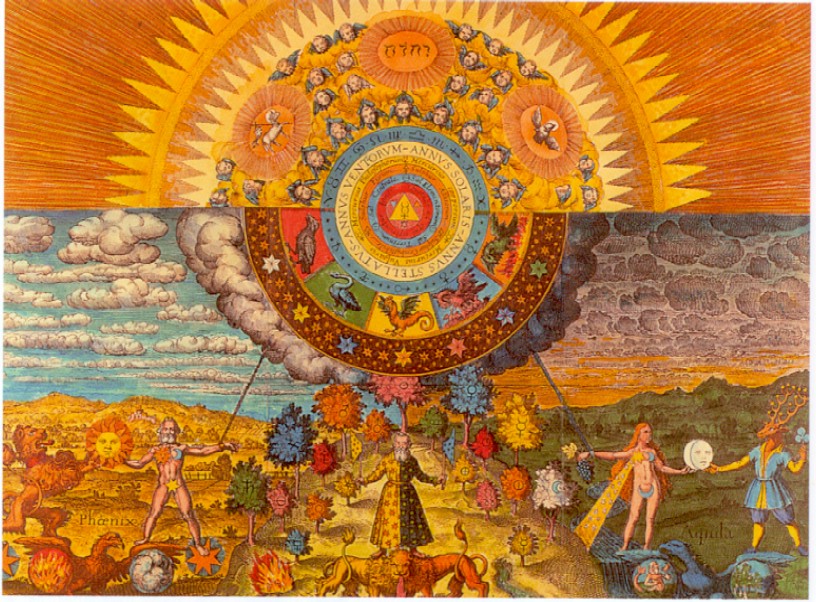

Listed as once in Sir Thomas Browne’s library is an edition of Kepler’s first published book, Mysterium Cosmographicum (Prague 1596) [1]. Kepler's ‘Mysteries of the Cosmos’ is the direct result of a vision the young mathematician experienced in which he believed God’s geometrical plan of the universe had been revealed to him. In his mystical revelation Kepler discovered the geometric solids as first described by Plato, the tetrahedron (4 sided) cube (6 sided) octahedron (8 sided) dodecahedron (12 sided) and icosahedron (20 sided) could each be uniquely represented by spherical orbs; each solid nesting within and encased in a sphere, would in total produce six layers, corresponding to the six known planets—Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn. By ordering the Platonic solids in their correct numerical sequence Kepler also discovered that the spheres could be placed at intervals which corresponded to his own calculations of the relative size of each planet’s path, as each planet circled the Sun.

Kepler’s great patron was the Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II (1552 -1612). During his long reign Rudolph II gathered at his relocated court at Prague, some of the most remarkable figures in the world of art and science. He was a generous patron to artists of the Mannerist school such as Archimboldo, Bartholomeus Spranger and Adrian de Vries, and to the astronomers Kepler and Tycho Brahe. Indeed, Rudolph II's pairing of the observational genius of the Dane Tycho Brahe to the mathematical gifts of Kepler has been considered his major contribution towards the advancement of astronomy.

Kepler’s residence at the court of the Holy Roman emperor from 1600 to 1612 resulted in his naming and dedicating his major work of scientific notation of planetary motion, the Rudulphine Tables, to Emperor Rudolph. Other visitors to the court of the melancholic, alchemy-loving Emperor and connoisseur of the arts include the Elizabethan mathematician and major figure of esotericism, John Dee (1527 -1608) and the poet Elizabeth Jane Weston.

Kepler’s residence at the court of the Holy Roman emperor from 1600 to 1612 resulted in his naming and dedicating his major work of scientific notation of planetary motion, the Rudulphine Tables, to Emperor Rudolph. Other visitors to the court of the melancholic, alchemy-loving Emperor and connoisseur of the arts include the Elizabethan mathematician and major figure of esotericism, John Dee (1527 -1608) and the poet Elizabeth Jane Weston.

The division between astrology and astronomy in Kepler’s day was quite blurred and not as sharply delineated as nowadays. Throughout his life Kepler supplemented his income by regularly publishing calendars which predicted future events from astrology. For the year 1595 he prophesied a particularly cold winter, an attack by the Turks from the south and a peasant uprising: all of which occurred.