Because throughout history to the present-day malaria is a world-wide killer of thousand of lives, the discovery of Peruvian Bark is a well-documented chapter in the history of medicine. The ability of bark from the cinchona tree to combat the symptoms of malaria, its eventual synthesizing as Quinine, and its subsequent world-wide usage is a vast subject. However one small footnote on Peruvian Bark in the history of British medicine may yet be added.

The discovery of Peruvian Bark's medicinal properties is attributed to several people. The Jesuit priest Agostino Salumbrino (1561–1642) who had trained as an apothecary is credited as among the first to observe that the indigenous Quechua or Inca people used a diffusion of the bark from the cinchona tree to alleviate the symptoms of malaria. Indeed the original Inca word for the cinchona tree bark, '

quina' or '

quina-quina' roughly translates as 'bark of bark' or 'holy bark'. It's also recorded that in 1638, the countess of Chinchon, the wife of a Peruvian viceroy used the bark of the cinchona tree to relieve the fever-induced shivering symptoms experienced during the onset of malaria to remedy a 'miracle cure'.

While its effect in treating malaria and also malaria-induced shivering was unrelated to its effect to control shivering from rigors, Peruvian Bark was nevertheless hailed as a successful medicine for malaria. Modern science has detected that the bark of the cinchona tree contains a variety of alkaloids, including the anti-malarial compound quinine which interferes with the reproduction of malaria-causing protozoa, and also quinidine, an antiarrhythmic.

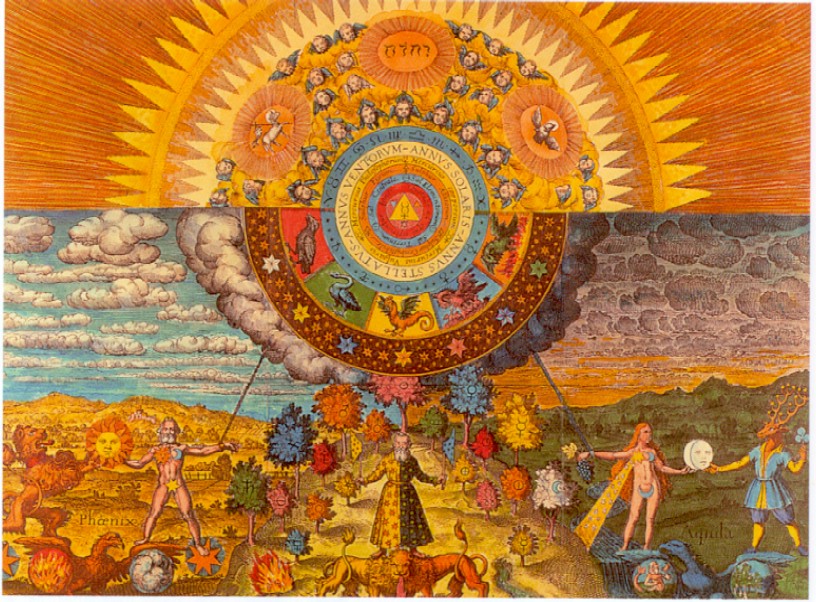

It was the Renaissance maverick alchemist Paracelsus who first urged the physician to examine and analyse substances from the vegetable, mineral and animal kingdoms in search of new medicines. By the seventeenth century with the colonization of South America by the Spanish and Portuguese, as well as migration to North America, an abundance of published reports upon the flora and fauna of the American continent became available to the physician. Foremost amongst such reports were those of the Jesuit missionaries who collected facts on all manner of botanical, geographical and social phenomena they encountered in their imperial-orientated colonization; including the discovery of the Cinchona tree's medical properties. For these reasons Peruvian Bark was also widely-known as 'Jesuits' powder'.

In 1658 the English weekly

Mercurius Politicus announced that: 'The excellent powder known by the name of 'Jesuits' powder' may be obtained from several London chemists'. However Peruvian Bark did not achieve full official approval and was not entered into the British Pharmacopoeia until 1677. This was mostly due to religious prejudices. Because it was known as 'Jesuits' Powder' it was associated with Catholicism. Even seemingly well-educated persons such as King Charles II, who took an active interest in the scientific inquiries of his age, sanctioning approval for the Royal Society was wary of 'Jesuit's Powder' because of its presumed association with Catholicism. However when suffering from malarial fever Charles II consulted Mr Robert Talbor, who had found fame for his miraculous cure of malaria. Talbor was obliged to give the King the bitter bark decoction in great secrecy. The treatment completely relieved the King from malarial fever and he rewarded Talbor with a life-times membership of the prestigious Royal College of Physicians.

Incidentally its alleged that Oliver Cromwell died of Malaria, refusing Jesuit's Powder as a remedy, simply because of his hatred of Catholicism! But as autopsy's were inaccurate in the seventeenth century, this allegation may simply be nothing more than Royalist propaganda enhancing the virtue of 'progressive monarchy' in contrast to the anti-monarchist Republic which was established by Cromwell.

Many physicians throughout England in the seventeenth century were interested in reports of the healing qualities of Peruvian Bark, in particular those who lived in regions prone to the spread of malaria; East Anglia with its many marshes, broads and Fens; geographic areas whose large tracts of low-laying land and many slow-flowing or stagnant stretches of water were ideal for the spread of the insect-borne virus. In correspondence dated 1667 to his youngest son, Dr. Thomas Browne of Norwich requested-

When you are at Cales, see if you can get a box of the Jesuits' powder at easier rate, and bring it in the bark, not in powder.

Its suggestive from this letter in his request to his son to obtain Jesuits' powder from a Continental source and not from London, that Dr.Browne may have been wary the thriving trade in Peruvian Bark could be vulnerable to dilution by apothecaries. Its also evident from his preference to obtain it from a continental source and insistence on bark and not powder that he was well-familiar with Peruvian Bark's composition.

Incidentally, it was for the entertainment and education of his youngest son Thomas that Sir Thomas Browne penned the Latin work

Nauchmachia, a descriptive account of a

Sea-battle in antiquity. Tragically however, young Midshipman Thomas was listed as lost at sea, presumed dead shortly after receiving this letter, he was most probably a fatality in the Anglo-Dutch naval-battle of Lowestoft in 1665.

But by far the most detailed document in British medical history of a physician's assessment of Peruvian Bark occurs in an undated and untitled note

concerning the Cortex Peruvianus or Quinana Peruve by Dr.Browne.

I am not fearful of any bad effect from it nor have I observed any that I could clearly derive from that as a true cause: it doth not so much good as I could wish or others expect, but I can lay no harm unto its charge, and I have known it taken twenty times in the course of a quartan. In such agues, especially illegitimate ones, many have died though they have taken it, but far more who have not made use of it, and therefore what ever bad conclusions such agues have I cannot satisfy myself that they owe their evil unto such medicines, but rather unto inward tumours inflammations or atonie of parts contracted from the distemper. Source: Brit. Mus. Sloane MS 1895

Because the above statement is undated with no addressee, there's no evidence for who, where or when Dr. Browne penned his assessment of Peruvian Bark. One would like to imagine that it was an assessment made for the benefit of King Charles II who had met and knighted Browne in 1671. It could theoretically have been surreptitiously passed onto Charles II via Browne's eldest son Edward who resided in London, had access to the Royal Court and was later President of the Royal College of Physicians. But it could as easily have been written for the benefit of any enquiring member of the gentry. In any case it demonstrates that not only was Dr. Browne well informed of the latest medical discoveries, even aware of excessive and 'illegitimate' usage of 'Jesuits' Powder', but was also able to independently assess such discoveries.

Flower of Chinchona pubescens