First performed in Budapest, a full century ago on May 12th 1917, Béla Bartók's ballet-pantomime The Wooden Prince is based upon a fairy-tale which focuses upon the themes of love and loneliness, the contrasting natures of men and women, the artist's relationship to creativity and the triumph of love over adversity.

The Hungarian composer Béla Bartók (1881-1945) is arguably one of the unhappiest examples of a composer who learned to live with neglect. Throughout most of his career, discouragement, the struggle to find an audience, failing health and chronic poverty, dominated his life. It was only after his death in 1945 that public recognition of his musical genius occurred.

The orchestral score of The Wooden Prince is the largest ever employed by Bartok. The composer calls for four flutes and two piccolos, four oboes and two english horns, four clarinets, E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, four bassoons and two contrabassoons, three saxophones, four horns, four trumpets and two cornets, three trombones and tuba, two harps, celesta, glockenspiel, xylophone, triangle, castanets, cymbals, side drum, bass drum, tam-tam, and strings. Its total performance time is approximately fifty minutes.

Termed a symphonic poem for dance by the composer, each individual dance of The Wooden Prince varies sharply in character. Highlights of the orchestral score include a terrifying Tolkien Ent-like march of trees, a jazz influenced dance upon waves featuring three saxophones, a playful dance of the princess in the forest scored for solo clarinet, harp and pizzicato strings, and a vigorous comic dance in which Bartok caricatures the movements of the wooden dummy prince lurching through abrupt shifts of tempo with a pulsing, repetitive rhythmic stamp.

The Wooden Prince reveals a number of influences upon the composer's maturing style. Its brilliant, original and colourful orchestration may have resulted from Bartok’s encounter with the repertoire of the Ballet Russe who visited Budapest with the Hungarian premieres in 1913 of Stravinsky’s two new ballets, The Firebird with its libretto based upon a conglomerate of Russian fairy tales, and the puppet-drama Petrushka.

The tone-poems of the Austrian composer Richard Strauss were also an influence upon Bartók who reportedly was stunned when first hearing Also Sprach Zarathustra (1890) at its Budapest premiere in 1902. Other influences include Bartok's careful study of Debussy’s scores at his friend and fellow composer Zoltan Kodály’s suggestion; and the discovery of Eastern European folk music, which had given him a second career as a pioneer ethnomusicologist.

The libretto of The Wooden Prince tells of a handsome young prince who sees a beautiful princess playing flirtatiously among the trees. He impulsively falls in love with her and struggles to win her heart. In his way stand the wishes of a fairy who wishes the prince to belong alone in her magical nature world, and who uses all her powers to prevent him from reaching the princess. In the third dance, termed a 'grand ballet', the forest itself, and then a river are summoned to turn the prince away from his goal, while in the distance the princess sits at her spinning wheel in the castle, oblivious to his effort. To gain her attention the prince fashions an image of himself, that he can lift above the trees for her to glimpse. He takes his crown, his sword, and, eventually, his golden hair, arranges them on a dummy, and watches as the princess instantly stops sewing and dashes down through the forest to find this handsome prince she has seen . The princess falls in love not with the real prince, but with the wooden dummy he has made, resulting in the dejected prince retreating into solitude. The wooden prince is brought to life by the fairy. The princess is disappointed once the dummy breaks down, catches sight of the real prince, and succeeds in regaining his heart. The prince abandons solitude for the embrace of lover. As the curtain falls the story ends with the lovers, now certain of their affection, standing quietly gazing into each other’s eyes.

Opening in the key of C major with distinct reference to the music of Richard Wagner's Rheingold, the introduction of The Wooden Prince displays great psychological mastery as its music slowly transforms from a mood of calm and tranquillity to one of full-blown tension and crisis.

Early in the ballet there is an uncanny evocation of a vast green forest and 'Water- music' in which Bartok vividly conjures a direct image of nature, applying the lessons of his impressionistic phase from the music of Debussy. The French composer's influence can be heard in the third dance of the ballet, Dance of the Waves which features three saxophones.

Opening in the key of C major with distinct reference to the music of Richard Wagner's Rheingold, the introduction of The Wooden Prince displays great psychological mastery as its music slowly transforms from a mood of calm and tranquillity to one of full-blown tension and crisis.

Early in the ballet there is an uncanny evocation of a vast green forest and 'Water- music' in which Bartok vividly conjures a direct image of nature, applying the lessons of his impressionistic phase from the music of Debussy. The French composer's influence can be heard in the third dance of the ballet, Dance of the Waves which features three saxophones.

The Belgian inventor Adolphe Sax's great contribution to music, the saxophone is featured in various other orchestral works, in particular those of French composers including Bizet in his L'Arlesienne suites dating from the 1870's, Ravel's Bolero (1928) as well as his orchestration of Mussorgsky's Pictures at an Exhibition (1922) and Debussy's Rhapsody for Saxophone and Orchestra (1903). Others who composed for the saxophone's distinctive voice include Rachmaninov in his Symphonic Dances (1940), his last ever composition, Vaughan Williams in Job, A Masque For Dancing (premiered in concert form in October 1930 at the Norfolk and Norwich Festival), Alexander Glazunov in his Concerto for Alto Saxophone and String Orchestra (1934) and Benjamin Britten in his Sinfonia da Requiem (1941).

One would have thought the saxophone to be the perfect instrument to depict a bustling metropolis in Bartok's subsequent work The Miraculous Mandarin, a story of sex, crime, murder and robbery, but in fact it's in the third dance of The Wooden Prince, entitled Dance of the Waves, with its three saxophones, that one of the earliest allusions in orchestral music to jazz can be heard.

The full sequence of dances in The Wooden Prince is as follows-

Part 1 [Prelude before the curtain rises] [Awakening of Nature]

First Dance - Dance of the princess in the forest.

Prince falls in love with her.

Prince falls in love with her.

Second Dance - Dance of the trees.

Trees, brought to life by the fairy, prevent the prince from reaching her.

Trees, brought to life by the fairy, prevent the prince from reaching her.

Third Dance - Dance of the Waves.

Fourth Dance - Dance of the princess with the wooden doll.

Fifth Dance - Princess pulls and tugs at the collapsing wooden prince.

Sixth Dance - She tries to attract the real Prince with seductive dancing.

Seventh Dance - Dismayed, the Princess attempts to hurry after the Prince. Prince and Princess embrace. Nature returns to a peaceful state.

In addition to the Italian story-teller Carlo Collodi's world-famous tale of the adventures of a wooden doll who becomes a boy, Pinocchio (1883) there are several ballets which feature a dummy or mannikin.

Leo Delibe's comic ballet Coppelia (1870), Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker (1892) based upon E.T.A. Hoffman's dark tale of 1816, and Stravinsky’s ground-breaking score for the Ballet Russe, Petrushka (1911) all feature a puppet or doll-like character. In the frenzied courtship dance of the princess with the puppet wooden prince Bartok utilizes exotic pentatonic harmonies and vigorous rhythms which are imitative of music in the score of Stravinsky's ballet, Petrushka.

A rare Hungarian video-clip of the moment the princess meets and dances with the wooden prince gives an idea of the intricate relationship between orchestral score and its choreography.

In the ballet's apotheosis the melody featured at the moment of the couple's final coming together is the Hungarian folk-song Fly, Peacock, quoted by Bartók in his First String Quartet and which Zoltán Kodály also quotes in his Peacock Variations.

The librettist of The Wooden Prince, Béla Balázs stated that the wooden puppet symbolizes the creative work of the artist, who puts all of himself into his work until he has made something complete, shining, and perfect. The artist himself, however, is left poor. as in that common and profound tragedy in which the creation becomes the rival of the creator, or the bitter-sweet dilemma in which a woman prefers the poem to the poet, the picture to the painter.

For the American music-historian Carl Leafstedt, the character of the Prince in Bartok’s ballet-pantomime is one of a symbolic chain of lonely selves which populate Bartok’s stage works. These include - Bluebeard, Judith, the Prince, Mimi and the Mandarin - all of whom are character’s seeking, and sometimes finding, however briefly, the release from solitude and the wholeness which love can bring. Leafstedt also noted - ‘Bartok extends and makes dramatically convincing, the prince’s gradual resignation and his ensuing embrace by Nature, as the fairy commands all things in the forest to pay homage to the disconsolate man. In so doing he enlarges the work’s symbolism: the prince’s grief is not merely a transitory grief over a lost opportunity, but a life-altering moment of realization. He sees, with a clarity never before experienced, the emptiness of humanity’s pursuit of love, and in that moment of realization gains symbolic admittance into a realm lying beyond reason, beyond suffering, where man, alone, can lay down the burdens of his soul on the breast of Nature. This apotheosis forms the emotional centre of Bartok’s ballet; it is surrounded on either side by the quicker, more extroverted dances of the princess and wooden prince. [1]

The literary genre of the fairy tale has become increasingly scrutinized and analysed. Taken seriously by the psychologist C.G. Jung, notably in his two essays dating from 1948, 'The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales' and in his analysis of the Brothers Grimm fairy-tale The Spirit in the Bottle in his The Spirit Mercurius 1948). Jung viewed fairy tales like myths to be spontaneous and naive products of soul which depicted different stages of experiencing the reality of the soul.

Jung's close associate, Marie-Louis von Franz (1915-98) considered fairy tales, along with alchemy, as examples of how the collective unconscious compensates for the one-sidedness of Christianity and its ruling god image. For Jungian analysts fairy tales are the 'purest and simplest expression of collective unconscious psychic processes' which represent the archetypes in their simplest, barest and most concise form'. 'In this pure form, the archetypal images afford us the best clues to the understanding of the processes going on in the collective psyche'.

Marie-Louis von Franz speculated - 'I have come to the conclusion that all fairy tales endeavour to describe one and the same psychic fact, but a fact so complex and far-reaching and so difficult for us to realize in all its different aspects that hundreds of tales and thousands of repetitions with a musician’s variation are needed until this unknown fact is delivered into consciousness; and even then the theme is not exhausted. This unknown fact is what Jung calls the Self, which is the psychic reality of the collective unconscious'.

An attentive reading of the complex orchestral score of Bartok's The Wooden Prince reveals a multitude of 'copy-book' motifs found in the soundtracks of numerous Hollywood films, including the genre of cartoon or animation. This is none too surprising for some of the most gifted of European composers, including Rachmaninov, Stravinsky, and Bohuslav Martinu, as well as Bartok, sought asylum in America before and during World War II. Their influence upon the development of American music cannot be under-estimated.

With its psychological motifs, impassioned moments and stark rhythms which originate from Bartok's study of Eastern European folk music known as Verbunkos, The Wooden Prince can now be recognised as not only an example of how European orchestral music influenced future music-making in America, but also as an orchestral work as radical and innovative as Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps (1913) in 20th century music.

Although productions of The Wooden Prince as a ballet are few in number today, it remains in the Hungarian dance repertoire to the present-day, as can be seen in the following video-clip.

The librettist of The Wooden Prince, Béla Balázs stated that the wooden puppet symbolizes the creative work of the artist, who puts all of himself into his work until he has made something complete, shining, and perfect. The artist himself, however, is left poor. as in that common and profound tragedy in which the creation becomes the rival of the creator, or the bitter-sweet dilemma in which a woman prefers the poem to the poet, the picture to the painter.

For the American music-historian Carl Leafstedt, the character of the Prince in Bartok’s ballet-pantomime is one of a symbolic chain of lonely selves which populate Bartok’s stage works. These include - Bluebeard, Judith, the Prince, Mimi and the Mandarin - all of whom are character’s seeking, and sometimes finding, however briefly, the release from solitude and the wholeness which love can bring. Leafstedt also noted - ‘Bartok extends and makes dramatically convincing, the prince’s gradual resignation and his ensuing embrace by Nature, as the fairy commands all things in the forest to pay homage to the disconsolate man. In so doing he enlarges the work’s symbolism: the prince’s grief is not merely a transitory grief over a lost opportunity, but a life-altering moment of realization. He sees, with a clarity never before experienced, the emptiness of humanity’s pursuit of love, and in that moment of realization gains symbolic admittance into a realm lying beyond reason, beyond suffering, where man, alone, can lay down the burdens of his soul on the breast of Nature. This apotheosis forms the emotional centre of Bartok’s ballet; it is surrounded on either side by the quicker, more extroverted dances of the princess and wooden prince. [1]

The literary genre of the fairy tale has become increasingly scrutinized and analysed. Taken seriously by the psychologist C.G. Jung, notably in his two essays dating from 1948, 'The Phenomenology of the Spirit in Fairytales' and in his analysis of the Brothers Grimm fairy-tale The Spirit in the Bottle in his The Spirit Mercurius 1948). Jung viewed fairy tales like myths to be spontaneous and naive products of soul which depicted different stages of experiencing the reality of the soul.

Jung's close associate, Marie-Louis von Franz (1915-98) considered fairy tales, along with alchemy, as examples of how the collective unconscious compensates for the one-sidedness of Christianity and its ruling god image. For Jungian analysts fairy tales are the 'purest and simplest expression of collective unconscious psychic processes' which represent the archetypes in their simplest, barest and most concise form'. 'In this pure form, the archetypal images afford us the best clues to the understanding of the processes going on in the collective psyche'.

Marie-Louis von Franz speculated - 'I have come to the conclusion that all fairy tales endeavour to describe one and the same psychic fact, but a fact so complex and far-reaching and so difficult for us to realize in all its different aspects that hundreds of tales and thousands of repetitions with a musician’s variation are needed until this unknown fact is delivered into consciousness; and even then the theme is not exhausted. This unknown fact is what Jung calls the Self, which is the psychic reality of the collective unconscious'.

An attentive reading of the complex orchestral score of Bartok's The Wooden Prince reveals a multitude of 'copy-book' motifs found in the soundtracks of numerous Hollywood films, including the genre of cartoon or animation. This is none too surprising for some of the most gifted of European composers, including Rachmaninov, Stravinsky, and Bohuslav Martinu, as well as Bartok, sought asylum in America before and during World War II. Their influence upon the development of American music cannot be under-estimated.

With its psychological motifs, impassioned moments and stark rhythms which originate from Bartok's study of Eastern European folk music known as Verbunkos, The Wooden Prince can now be recognised as not only an example of how European orchestral music influenced future music-making in America, but also as an orchestral work as radical and innovative as Stravinsky's Le Sacre du Printemps (1913) in 20th century music.

Although productions of The Wooden Prince as a ballet are few in number today, it remains in the Hungarian dance repertoire to the present-day, as can be seen in the following video-clip.

Bibliography and Notes

Bartok Orchestral Music John McCabe BBC pub. 1974

[1] The Cambridge Companion to Bartok edited by Amanda Bayley pub. CUP 2001 includes - The Stage Works: Portraits of loneliness by Carl Leaftstedt

Discography

The Wooden Prince and Cantata Profana - Chicago Symphony Orchestra and chorus conducted by Pierre Boulez DGG 1991

Naxos - The Wooden Prince - Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra conducted by Marin Alsop 2008

Illustrations

Top - A photo of Nikolay Boyarchikov's 1966 choreographic version of The Wooden Prince at the Mikhailovsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg.

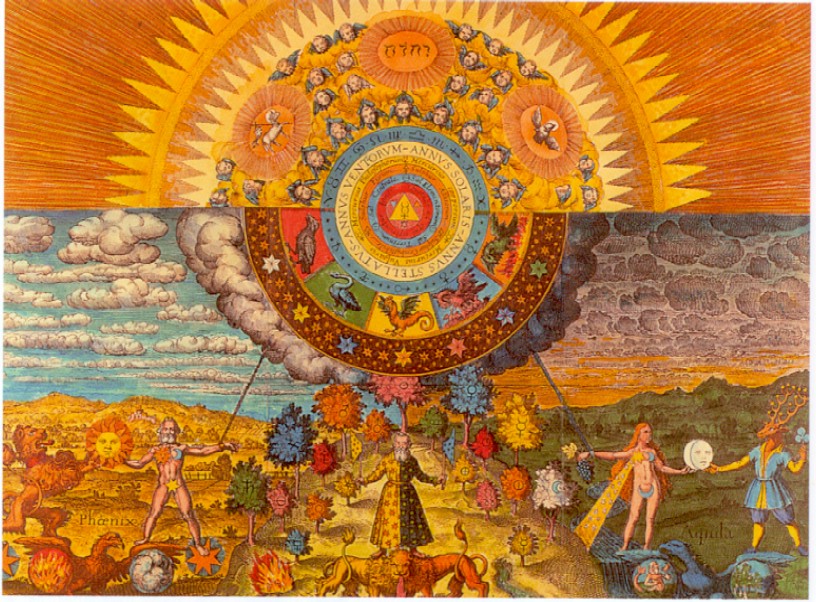

Next - Cover of 1917 Budapest publication of Béla Balázs The Wooden Prince.

An essay for Carl living in Hungary.

Bartok Orchestral Music John McCabe BBC pub. 1974

[1] The Cambridge Companion to Bartok edited by Amanda Bayley pub. CUP 2001 includes - The Stage Works: Portraits of loneliness by Carl Leaftstedt

Discography

The Wooden Prince and Cantata Profana - Chicago Symphony Orchestra and chorus conducted by Pierre Boulez DGG 1991

Naxos - The Wooden Prince - Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra conducted by Marin Alsop 2008

Illustrations

Top - A photo of Nikolay Boyarchikov's 1966 choreographic version of The Wooden Prince at the Mikhailovsky Theatre, Saint Petersburg.

Next - Cover of 1917 Budapest publication of Béla Balázs The Wooden Prince.

An essay for Carl living in Hungary.