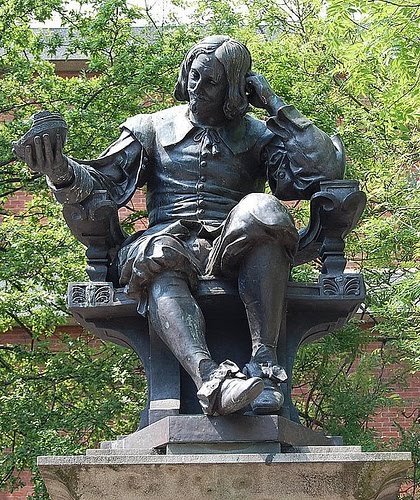

Green hypothesised that one possible reason why Sir Thomas Browne's prose is stylistically unlike any of his contemporaries may have been due to an empirical enquiry into the effects of drugs. He also noted that the two Discourses of 1658, Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus were penned by a Royalist who was under intense emotional and psychological distress during the Interregnum and Protectorate of Cromwell (1650-1660) and proposed that the rhapsodic fifth and final chapter of both Discourses may have been written in a trance-like condition.

It was during Browne's era, the seventeenth century, which saw the discovery of the tobacco-leaf and coffee-bean, drugs which, along with alcohol, continue to be acceptable and widely consumed throughout the world today. As a physician Browne was licensed to obtain opium, the only available pain-killer and tranquilliser in the medicine of his era. Widely in use since the sixteenth century, the Swiss alchemist-physician Paracelsus (1493-1541) was amongst the earliest advocates of opium. Such was its widespread usage that by the seventeenth century Dr. Thomas Sydenham (1624-89) the so-called 'Father of English medicine' whose books are well-represented in Browne’s vast library, declared-

'Among the remedies which has pleased the Almighty God to give to man to relieve his sufferings, none is so universal and so efficacious as opium.'

Opium was used in the seventeenth century to relieve a variety of medical conditions, including disorders such as dysentery and respiratory ailments. There can be little doubt that in the course of his career Browne had the opportunity to observe the physical and mental effects of opium. His commonplace notebooks even record various experiments of dosages of opium upon animals, a vital and necessary precaution before administering opium to his patients.

'Three grains of opium works strongly upon a dog. Observe how much will take place with a horse....Fishes are quickly intoxicated with baits: in what quantity with opium ? What quantity will take, in birds and animals with little heads ? From two grains unto five we have given unto a cockerel, without any discernable sophition... four unto a crow without visible effect. Six and eight unto dogs making them dull not profoundly to sleep....Five grains we have also given unto turkeys without effect of sleep....Five grains unto a young kestrel, did seem the like vertiginous and a little more sleepy; not profoundly. Five unto a young heron did nothing. [2]

It's in Urn-Burial (1658) that Browne employs highly original medical-philosophical imagery, which must surely have been acquired from observing first-hand the psychological effects of opium, declaring-

'There is no antidote against the Opium of Time which temporally considereth all things.'

Browne also poetically links the botanical source of opium with his discourse’s theme of the unknowingness of the human condition when stating - 'The iniquity of oblivion blindly scattereth her Poppy'; while also declaiming - 'Oblivion is not to be hired.'

Although the popular image of Browne is that of the orthodox physician, he was in fact one of the earliest of English doctor's to know of the hedonistic cocktail of sex and drugs, writing of such indulgences that -

'the effect of eating Opium is not so much as to invigorate themselves in coition, as to prolong the Act, and spin out the motions of carnality.' [3]

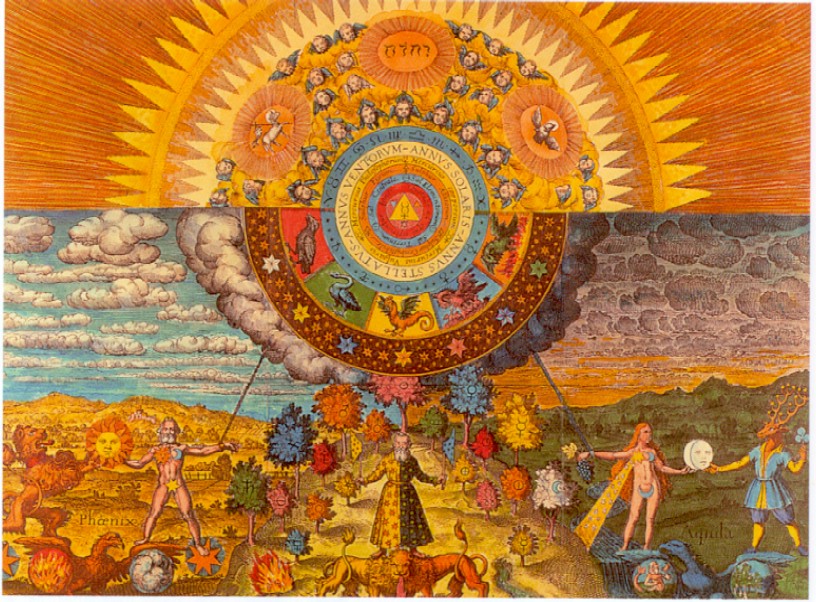

Throughout the history of alchemy and early chemistry there was a considerable knowledge of substances, minerals and drugs. Today, there are laws prohibiting the recreational usage of drugs, laws which continue to be as ineffective as those of America’s Prohibition era, laws which do little more than sponsor crime by creating a lucrative black market, exposing the vulnerable to adulterated and potentially hazardous substances, without either protecting or educating consumers to the possible consequences upon health, and unfairly criminalizing people, thus seriously damaging and wasting skills and life-opportunities.

Throughout the history of alchemy and early chemistry there was a considerable knowledge of substances, minerals and drugs. Today, there are laws prohibiting the recreational usage of drugs, laws which continue to be as ineffective as those of America’s Prohibition era, laws which do little more than sponsor crime by creating a lucrative black market, exposing the vulnerable to adulterated and potentially hazardous substances, without either protecting or educating consumers to the possible consequences upon health, and unfairly criminalizing people, thus seriously damaging and wasting skills and life-opportunities.

No matter how much some may object to Peter Green’s hypothesis that the unique literary style of the discourses Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus with their thematic progression of a 'soul journey' from the Grave to Garden may have originated from experimentation with drugs, it nevertheless remains a curious coincidence that in the nineteenth century Browne's literary works were 'rediscovered' and admired by the early Romantic figures of Charles Lamb, Thomas De Quincey and Coleridge; all of whom frequently indulged in laudanum, the alcohol-based tincture of opium, which was widely available in the nineteenth century.

The idea that a major literary figure who was a moralist, devout Christian and respectable doctor may have written sections of his 'deep, stately, majestic' prose (De Quincey), with its slow, sombre contemplation upon Death and the afterlife, under the influence of Opium, would have been acceptable to the English essayist Thomas De Quincey, who, in his Confessions of an English Opium-eater (1821) before a visit to the opera while under the influence of opium stated-

‘I do not recollect more than one thing said adequately on the subject of music in all literature: it is a passage in Religio Medici of Sir T. Brown; and, though chiefly remarkable for its sublimity, has also a philosophical value; inasmuch as it points to the true theory of musical effects.'

But perhaps the greatest portrait of opium's effects in music occurs in De Quincey's contemporary, the French composer Hector Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique (1830).

Berlioz's five movement symphony introduced a radical and distinctly French approach to orchestration and melody, quite unlike the Viennese tradition, although also indebted to Beethoven's programmatic Pastoral symphony. In Berlioz's programmatic symphony, the romantic hero while under the influence of opium, conjures up a reverie of his beloved, catches a glimpse of her at a Ball, visits the countryside with her, and in a paroxysm of passion, murders her. He's sent to the guillotine for his crime, and in the symphony's 5th and final movement he dreams of attending a Witch's Sabbath, in music with decidedly hallucinatory effects.

In complete contrast to Urn-Burial's 'vast undulations of sound' and declamatory 'full Organ-stop' baroque prose, Browne's discourse The Garden of Cyrus has predominately visual imagery. Frequently breathless and fractured in style, paragraph succeeds paragraph in a rapid procession of examples; firstly from gardens in antiquity, then art objects, followed by examples in nature in its long central chapter, and finally in mystical analogies involving astrology and the kabbalah. These examples in turn involve the inter-related symbols of the numbers five and ten, the quincunx pattern, along with its variants including lozenge-shape, the figure X, and criss-cross and network patterns. All of which are all paraded before the reader as exemplary of 'how God geometrizes'.

The distinguished Brunonian scholar and Dean Emeritus of Princeton University, USA, Jeremiah S. Finch (1910-2005) when examining a manuscript edition of The Garden of Cyrus described it as, 'a headlong scrawl, a quick hand and moving imagination, thinking quicker than his hand' with 'no less than 8 deletions occurring within 27 lines'. [4] Such uncharacteristic haste is suggestive of one who urgently wishes to impart a new insight. A fine example of Browne’s near stream-of-consciousness purple prose occurs in the paragraph -

In Chess-boards and Tables we yet find Pyramids and Squares, I wish we had their true and ancient description, far different from ours, or the Chet mat of the Persians, and might continue some elegant remarkables, as being an invention as High as Hermes the Secretary of Osyris, figuring the whole world, the motion of the Planets, with Eclipses of Sun and Moon.

One possible reason for the uncharacteristic composition of The Garden of Cyrus may have been due to Browne's excitement at 'discovering' the quincunx pattern could be discerned throughout the universe. Such excitement is not dissimilar to those 'discovering' the meaning of life while under the influence of hallucinogens. Interestingly, the very word 'hallucination’ is recorded in the Oxford English dictionary as first used by Browne, one of hundred of words he introduced into the English language.

Empirical experimentation with drugs may have been the source of Browne's experiencing a 'Soul Journey' not unlike the legendary Hermes Trismegistus of Hermetic philosophy and his journey through the planetary spheres. Other 'Soul-journeys' of antiquity include Plato's Myth of Er and Cicero's 'Dream of Scipio', in which the cosmic voyager hears the heavenly music of the spheres. Alternatively, Browne may have read Iter Ecstaticum Kirceranium (1660) which describes how the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher (1602-80) after listening to three lute-players, was led by the spirit Cosmiel in an ecstatic journey through the planetary spheres. Browne owned several books by Plato and Cicero, as well as several by Kircher, including Iter Ecstaticum (ed. Gaspar Schott). [5]

For the empiricist, as for the alchemist, the self and its sensory impressions were the bed-rock of all experimentation. Whether Browne’s empirical nature ever included experimentation with drugs will never be truly known, however he may done so either accidentally, or as part of his medical studies, or even as part of a misguided alchemical quest. But as the Swiss psychologist C.G.Jung (1875-1961) long before sixties drug culture, stated -

For the empiricist, as for the alchemist, the self and its sensory impressions were the bed-rock of all experimentation. Whether Browne’s empirical nature ever included experimentation with drugs will never be truly known, however he may done so either accidentally, or as part of his medical studies, or even as part of a misguided alchemical quest. But as the Swiss psychologist C.G.Jung (1875-1961) long before sixties drug culture, stated -

One only has to think what it means if in the misery and incertitude of a moral or philosophical dilemma one has a quinta essentia, a lapis or a panacea so to say in one's pocket ! We can understand this deus ex machina the more easily when we remember with what passion people today believe that psychological complications can be made magically to disappear by means of hormones, narcotics, insulin shocks and convulsion therapy. The alchemists were as little able to perceive the symbolical nature of their ideas of the arcarnum as we to realise that the belief in hormones and shocks is a symbol. [6]

Nor is it impossible that Browne may have known of the hallucinogenic properties of psilocybin mushrooms. He took an interest in fungi, and in a letter consisting of several paragraphs upon fungus to Christopher Merritt, makes mention of the highly toxic Deadly Nightcap -

The fungi Phalloides I found not very far from Norwich, large and very fetid......I have a part of one dried still by me. Fungus rotundus major I have found about ten inches in diameter, and have half a dried one by me. [7]

Sir Thomas Browne was also aware that contaminated rye bread can produce extraordinary psychological effects. When digested contaminated rye bread can produce effects similar to that of the entheogen LSD. Ergot itself does not contain lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) but it does contain its precursor, ergotamine. Browne is not always credited with familiarity with the medical condition of ergotism, however he did introduce the word ‘ergotism', as in meaning the effects of ergot poisoning, into English language, stating in his advisory work Christian Morals (circa 1675)

'Natural parts and good Judgement rule the World. States are not governed by ergotisms.' [8]

Ergot poisoning has several names. These include St. Anthony's fire and St. Vitus dance. According to Wikipedia - 'Human poisoning due to the consumption of contaminated rye bread made from ergot-infected grain was common in Europe throughout the Middle Ages. It occurred primarily in Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries and involved groups of people dancing erratically, sometimes thousands at a time. The mania affected men, women, and children who danced until they collapsed from exhaustion. One of the first major outbreaks was in Aachen, in 1374, and it quickly spread throughout Europe; one particular outbreak occurred in Strasbourg in 1518. Affecting thousands of people across several centuries, dancing mania was not an isolated event, and was well documented in contemporary reports. It was nevertheless poorly understood, and remedies were based on guesswork. Generally, musicians accompanied dancers, to help ward off the mania, but this tactic sometimes backfired by encouraging more people to join in. [9]

Dancing is a spontaneous and natural expression of ecstasy. The citizens of Strasbourg and elsewhere in Europe during the Middle Ages however would not have known they were under the influence of food which had chemically altered and would have attributed their ecstasy to religious emotions. Modern society is not immune from similar outbreaks of crowd hysteria, technically known as mass psychogenic illness. The population of the United States of America in particular seems to be vulnerable to such outbreaks. In 1931 wide-spread panic occurred when it was believed aliens from outer space had invaded America, following a radio broadcast of H.G.Well's 'War of the Worlds'. And at the present-time of writing an outbreak of a craze involving threatening and creepy clowns has occurred in the USA, resulting in public hysteria.

In conclusion, together Browne's diptych discourses Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus may be defined as a work of transcendent synthesis; together their thematic concerns, imagery and literary style share a number of characteristics associated with altered states of consciousness. These include - an awareness of the paradox of time and space, a profound sense of the sacredness of creation, a heightened consciousness of one's own and other's personality, an intense, absorbed contemplation of art, in particular colour and sound, and a near overwhelming awareness of one's place in nature and the cosmos, allegedly.

In the final analysis it hardly matters whether or not Browne ever took drugs. The complex combination of his deep religiosity, rigorous scientific enquiry, his capacious and retentive memory, in conjunction with his omnivorous reading habits, along with his highly developed aesthetic sensibility involving all the senses, (he enjoyed viewing paintings, listening to music, good food and sweet odours), while also possessing a rich and fertile artistic imagination, guarantees Sir Thomas Browne will forever be a perennial and paradoxical figure in the spheres of world literature, science and philosophy.

Possessing all the aforementioned gifts which he fully integrated in his spirituality, intellect, artistic imagination and character, there was hardly any need whatsoever for Sir Thomas Browne to take drugs !

Notes

[1] Peter Green Writers and their Work no. 108 pub. Longmans and co. 1959

[2] The miscellaneous writings of Sir Thomas Browne ed. Geoffrey Keynes pub. Faber and Faber 1931

[3] Pseudodoxia Epidemica Book 8 Chapter 7

[4] Sir Thomas Browne: A Doctor's Life of Science and Faith by Jeremiah Finch New York 1950.

[5] A Facsimile of the 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue of Sir Thomas Browne and his son Edward's Libraries. Introduction, notes and index by J.S. Finch (E.J. Brill: Leiden, 1986) page 30. no. 52

[6] Collected Works of C.G. Jung Volume 14 paragraph 680

[7] Letter to Dr. Merritt August 18 1668

[8] Christian Morals Part 2 Section 4.

[9] Extract from Dancing Mania Wikipedia.

See also

Mass psychogenic illness

Peruvian bark

Obituary of J.S. Finch

Essay dedicated to autodidact, intrepid psychonaut, voracious reader and bon viveur, Tom Bombadil of Ecuador.

[1] Peter Green Writers and their Work no. 108 pub. Longmans and co. 1959

[2] The miscellaneous writings of Sir Thomas Browne ed. Geoffrey Keynes pub. Faber and Faber 1931

[3] Pseudodoxia Epidemica Book 8 Chapter 7

[4] Sir Thomas Browne: A Doctor's Life of Science and Faith by Jeremiah Finch New York 1950.

[5] A Facsimile of the 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue of Sir Thomas Browne and his son Edward's Libraries. Introduction, notes and index by J.S. Finch (E.J. Brill: Leiden, 1986) page 30. no. 52

[6] Collected Works of C.G. Jung Volume 14 paragraph 680

[7] Letter to Dr. Merritt August 18 1668

[8] Christian Morals Part 2 Section 4.

[9] Extract from Dancing Mania Wikipedia.

Mass psychogenic illness

Peruvian bark

Obituary of J.S. Finch

Essay dedicated to autodidact, intrepid psychonaut, voracious reader and bon viveur, Tom Bombadil of Ecuador.

No comments:

Post a Comment