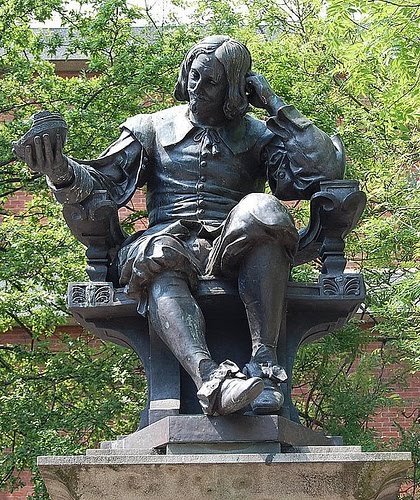

Today on the birth and death anniversary of the English seventeenth century literary figure, Sir Thomas Browne, its rewarding to look at aspects of the hermetic philosopher's little explored relationship to the kabbalah.

Its only recently that the many prejudices and misapprehensions which once surrounded the vital role and influence which esoteric ideas such as astrology, alchemy and the kabbalah wielded in intellectual history have finally eroded. It’s only now possible to acknowledge Sir Thomas Browne’s interest in the kabbalah as an integral component of his status as one of 17th century Europe's most learned scholars of comparative religion; his Discourse The Garden of Cyrus (1658) reveals him to be none other than one of England’s leading literary exponents of the kind of hermetic philosophy which John Dee (1527-1608) and his eldest son Arthur Dee (1579-1651) both vigorously pursued.

One of the most valued of all hermetic traditions amongst adepts such as the Dee's, was the mystical Jewish teachings known as the kabbalah, in which number and letter assume magical significance. It was believed necessary to acquire knowledge of the Hebrew language by devout scholars such as Browne, primarily in order to read the word of God as revealed to his prophets in the original written form, namely Hebrew.

A familiarity with the 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue (an indispensable document in the study of Browne) swiftly reveals the names of leading Hebrew scholars, along with Latin and Greek, Hebrew and even Ethiopian dictionaries as once shelved in his library. Rather unsurprisingly there are also some jolly thumping big books on the kabbalah listed as once in Browne's library [1]. The two humanist scholars who first promoted esoteric topics as worthy of enquiry in the Renaissance, Marsilio Ficino (1433-99) and his successor, Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) are both represented, as is, 'the supreme representative of Hermeticism in Post-Reformation Europe', Athanasius Kircher (1602-80).

One of the most valued of all hermetic traditions amongst adepts such as the Dee's, was the mystical Jewish teachings known as the kabbalah, in which number and letter assume magical significance. It was believed necessary to acquire knowledge of the Hebrew language by devout scholars such as Browne, primarily in order to read the word of God as revealed to his prophets in the original written form, namely Hebrew.

A familiarity with the 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue (an indispensable document in the study of Browne) swiftly reveals the names of leading Hebrew scholars, along with Latin and Greek, Hebrew and even Ethiopian dictionaries as once shelved in his library. Rather unsurprisingly there are also some jolly thumping big books on the kabbalah listed as once in Browne's library [1]. The two humanist scholars who first promoted esoteric topics as worthy of enquiry in the Renaissance, Marsilio Ficino (1433-99) and his successor, Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) are both represented, as is, 'the supreme representative of Hermeticism in Post-Reformation Europe', Athanasius Kircher (1602-80).

While Ficino attempted to reconcile the wisdom of Hermeticism and Plato with the teachings of the Church, his successor, Pico della Mirandola (1463-94) focussed on promoting study of the Kabbalah. Pico della Mirandola was the first to seek in the Kabbalah proof of the Christian mysteries. Besides Greek and Latin he knew Hebrew, Chaldean and Arabic; his Hebrew teachers introduced him to the kabbalah. One of the most startling of Mirandola’s proposals was that no science gives surer conviction of the divinity of Christ than "magia" (i.e. the knowledge of the secrets of the heavenly bodies) than esoteric Jewish teaching. Mirandola was an influential figure in the history of Western esotericism and would be taken seriously a century later in England when declaring, 'Angels only understand Hebrew' by would-be Angel conjurers. John and Arthur Dee.

However, the pre-eminent book which influenced the development of Christian kabbalah and which is listed in Browne's library, was by Francesco Giorgi (1467-1540). His book De Harmonia Mundi (1525) is a complex synthesis of Christianity, the kabbalah and the angelic hierarchies.

The seminal British scholar of esoteric philosophy, Francis Yates (1899-1981) wrote of Giorgi -

The seminal British scholar of esoteric philosophy, Francis Yates (1899-1981) wrote of Giorgi -

'Giorgi's Cabalism, though primarily inspired by Pico della Mirandola, was enriched by the new waves of Hebrew studies which Venice with its renowned Jewish community was an important centre. Cabalistic writings flooded into Venice following the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. Giorgi grafts Cabalist influence onto the traditions of his order. He develops that correlation between Hebrew and Christian angelic systems, already present in Pico, to a high degree of intensity. For Giorgi, with his Franciscan optimism, the angels are close indeed, and Cabala has brought them closer. He accepts the connections between angelic hierarchies and planetary spheres, and rises up happily through the stars to the angels, hearing all the way those harmonies on each level of the creation imparted by the Creator to his universe, founded on number and numerical laws of proportion The secret of Giorgi's universe was number, for it was built, so he believed, by its Architect as a perfectly proportioned Temple, in accordance with unalterable laws of cosmic geometry'.....In Giorgi's Christian Cabala, the angelic hierarchies of Pseudo-Dionysius are connected with the Sephiroth of the Cabala... The planets are linked to the angelic hierarchies and the Sephiroth'.[2]

It was while in London, engaged in a diplomatic errand that the Franciscan monk Giorgi met the Elizabethan magus John Dee. There is thus a quite distinct traceable link between the Renaissance founders of the Neoplatonic, Neopythagorean and Cabalist traditions, namely Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola via the Franciscan monk Giorgio and his advocacy of the Cabala to John Dee via his son Arthur Dee to Sir Thomas Browne. This hypothesis is strengthened by the fact that that both John Dee and Browne each possessed a copy of Giorgio’s highly-influential work De Harmonia Mundi. Unless that is Arthur Dee bequeathed his father's copy of De Harmonia Mundi to Browne [2] but that would be no less of a strong link!

Browne’s respect for the Kabbalah can be discerned in his encyclopaedia Pseudodoxia Epidemica where one encounters the somewhat indignant exclamation -

Astrologers, which pretend to be of Cabala with the Stars (such I mean as abuse that worthy Enquiry) have not been wanting in their deceptions; [4]

Browne’s understanding of the kabbalah included an awareness that in the Hebrew alphabet each letter also denotes a number, of either fortunate or unlucky disposition thus-

Cabalistical heads, who from that expression in Esay (Isaiah 34:4) do make a book of heaven, and read therein the great concernments of earth, do literally play on this, and from its semicircular figure, resembling the Hebrew letter כ Caph, whereby is signified the uncomfortable number of twenty, at which years Joseph was sold, which Jacob lived under Laban, and at which men were to go to war: do note a propriety in its signification; as thereby declaring the dismal Time of the Deluge. [5]

There’s also evidence in Pseudodoxia Epidemica that Browne was familiar with one of the earliest and most influential of all kabbalistic texts, the legendary Book of Splendour. Also known as the Zohar (Hebrew: זֹהַר, lit. "Splendor" or "Radiance") the foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought it consists of commentary on aspects of the Torah (the five books of Moses) mythical cosmogony and mystical psychology. The Zohar also contains a discussion of the nature of God, the origin and structure of the universe, the nature of souls, redemption, the relationship of Ego to Darkness and "true self" to "The Light of God", and the relationship between the "universal energy" and man. [6]

Browne tantalizingly alludes to Moses de León (c. 1250 – 1305) known in Hebrew as Moshe ben Shem-Tov (משה בן שם-טוב די-ליאון), the Spanish rabbi and Kabbalist considered to be the author of the Zohar in this remark-

'.....as M. Leo the Jew has excellently discoursed in his Genealogy of Love: defining beauty a formal grace, which delights and moves them to love which comprehend it. This grace say they, discoverable outwardly, is the resplendent and Ray of some interior and invisible beauty, and proceeds from the forms of compositions amiable.' [7]

Although its recorded that as early as 1934 Joseph Blau wrote upon Browne’s interest in the Kabbalah, amazingly, only in 1989 was it recognised that the leading scholar of Hebrew and the Kabbalah in 17th century Germany, Christian Knorr von Rosenroth (1636-89) has an interesting relationship to Browne.[8] The German scholar Von Rosenroth devoted many hours of his somewhat short life, completing what must have been a true labour of love, translating in total over 200,000 words of Browne’s colossal encyclopaedia Pseudodoxia Epidemica into German, completing his task in 1680 for publication in Frankfurt and Leipzig. Whether Browne was informed of this translation, late in his life isn't known, but it seems unlikely he wouldn't hear of it.

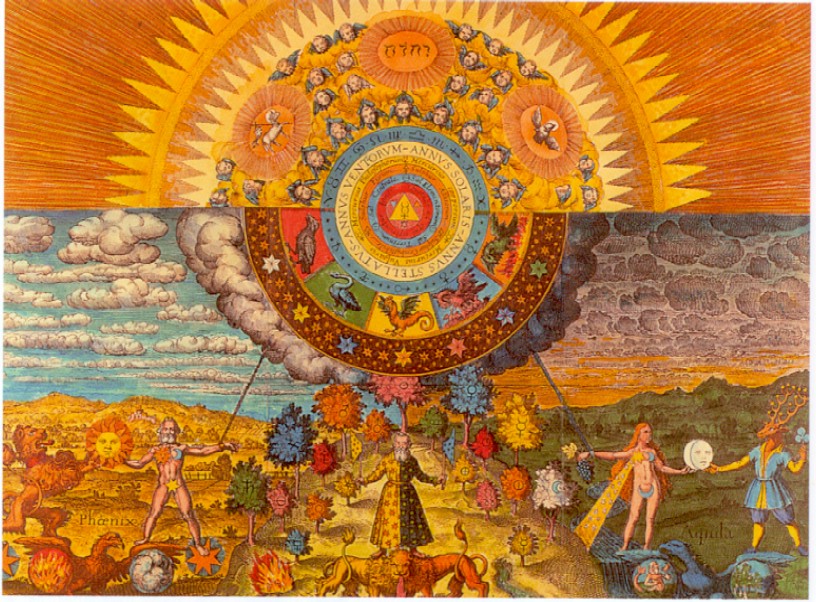

Browne’s esoteric inclinations are given full vent in his phantasmagorical discourse and supreme work of hermetic philosophy in English literature, The Garden of Cyrus (1658) in which the Kabbalah is alluded to several times.

The opening paragraph of chapter 3 of The Garden of Cyrus sees Browne move swiftly on from examples of the Quincunx pattern in gardening and art, to those in nature. In a paragraph of humorous and cosmic prose, he alludes to a French contemporary, the Hebrew scholar, astrologer and librarian to Cardinal Richelieu, Jaques Gafferel (1601-81). Browne was particularly interested in Gaffarel’s best-selling book, which had been translated into English as Unheard of Curiosities in 1650 in which the French kabbalist proposes an alternative to the Babylonian-Greek circle of animals or Zodiac.

Using the stars quite differently from the Babylonian-Greek circle of animals or Zodiac, Gaffarel describes how the letters of the Hebrew alphabet can be traced in the stars of the night-sky. Browne includes Gaffarel along with esoteric concepts of the 'music of the spheres' and the cosmic harmony of Pan's pipes as worthy of credulity thus-

The opening paragraph of chapter 3 of The Garden of Cyrus sees Browne move swiftly on from examples of the Quincunx pattern in gardening and art, to those in nature. In a paragraph of humorous and cosmic prose, he alludes to a French contemporary, the Hebrew scholar, astrologer and librarian to Cardinal Richelieu, Jaques Gafferel (1601-81). Browne was particularly interested in Gaffarel’s best-selling book, which had been translated into English as Unheard of Curiosities in 1650 in which the French kabbalist proposes an alternative to the Babylonian-Greek circle of animals or Zodiac.

Using the stars quite differently from the Babylonian-Greek circle of animals or Zodiac, Gaffarel describes how the letters of the Hebrew alphabet can be traced in the stars of the night-sky. Browne includes Gaffarel along with esoteric concepts of the 'music of the spheres' and the cosmic harmony of Pan's pipes as worthy of credulity thus-

Could we satisfy ourselves in the position of the lights above, or discover the wisdom of that order so invariably maintained in the fixed Stars of heaven; Could we have any light, why the stellary part of the first mass, separated into this order, that the Girdle of Orion should ever maintain its line, and the two Stars in Charles's Wain never leave pointing at the Pole-Star, we might abate the Pythagorical Music of the Spheres, the sevenfold Pipe of Pan; and the strange Cryptography of Gaffarell in his Starry Book of Heaven.

In his wide-ranging discourse of analogies and correspondences connecting the number five and quincunx pattern in art, nature and 'mystically considered’ Browne lets rip in rapid, near breathless enquiry, making note upon gardening, generation, germination, grafting, heredity, birth-marks, physiognomy, astrology, chess and skittles, archery and knuckle-stones, Egyptian hieroglyphs, architecture, optics, the camera obscura, acoustics and the healing power of music, among other topics of interest to the worthy 17th century Norwich physician.

Given its free-ranging imaginative associations its almost predictable that the alphabet mysticism of the Kabbalah is included in this unique and idiosyncratic literary work. Browne speculates upon the properties of the letter He, the 5th letter in the Hebrew alphabet. His kabbalist enquiry includes one of the earliest recorded usages of the word ‘archetype’ in English.

The same number in the Hebrew mysteries and Cabalistical accounts was the character of Generation; declared by the letter He, the fifth in their Alphabet; According to that Cabalisticall Dogma: If Abram had not had this Letter added unto his Name he had remained fruitlesse, and without the power of generation: Not only because hereby the number of his Name attained two hundred forty eight, the number of the affirmative precepts, but because as increated natures there is a male and female, so in divine and intelligent productions, the mother of Life and Fountain of souls in Cabalistically Technology is called Binah; whose Seal and Character was He. So that being sterile before, he received the power of generation from that measure and mansion in the Archetype; and was made conformable unto Binah. [9] -

The same number in the Hebrew mysteries and Cabalistical accounts was the character of Generation; declared by the letter He, the fifth in their Alphabet; According to that Cabalisticall Dogma: If Abram had not had this Letter added unto his Name he had remained fruitlesse, and without the power of generation: Not only because hereby the number of his Name attained two hundred forty eight, the number of the affirmative precepts, but because as increated natures there is a male and female, so in divine and intelligent productions, the mother of Life and Fountain of souls in Cabalistically Technology is called Binah; whose Seal and Character was He. So that being sterile before, he received the power of generation from that measure and mansion in the Archetype; and was made conformable unto Binah. [9] -

Its also in the 'mystically considered' chapter 5 of The Garden of Cyrus that Browne speculates upon the healing power of music upon the mind, using kabbalistic analogy thus-

Why the Cabalistical Doctors, who conceive the whole Sephiroth, or divine emanations to have guided the ten-stringed Harp of David, whereby he pacified the evil spirit of Saul, in strict numeration do begin with the Perihypate Meson, or si fa ut, and so place the Tiphereth answering C sol fa ut, upon the fifth string: [10]

Curiously the Sephirotic Tree of the kabbalah and the Quincunx pattern as illustrated in the frontispiece of The Garden of Cyrus have both been viewed as examples of 'stepped-down versions' of Indra's Net. In Hindu mythology the god Indra has a net which has a multifaceted jewel fixed at each knot, each jewel in turn reflects all the other jewels suspended in the net. The image of Indra's net is sometimes used to describe the interconnected relationship of the entire universe, not unlike either the Sephiroth tree of the kabbalah or Browne's intention in citing numerous examples of the Quincunx pattern in art, nature and mystically.

Curiously the Sephirotic Tree of the kabbalah and the Quincunx pattern as illustrated in the frontispiece of The Garden of Cyrus have both been viewed as examples of 'stepped-down versions' of Indra's Net. In Hindu mythology the god Indra has a net which has a multifaceted jewel fixed at each knot, each jewel in turn reflects all the other jewels suspended in the net. The image of Indra's net is sometimes used to describe the interconnected relationship of the entire universe, not unlike either the Sephiroth tree of the kabbalah or Browne's intention in citing numerous examples of the Quincunx pattern in art, nature and mystically.

Browne however was not a solitary figure in his interest in the kabbalah in 17th century England. The Cambridge Platonists, in particular its leading members, Henry More (1614-87) the author of Conjectura Cabbalistica (1653), and Ralph Cudworth (1617-88) also had a keen interest in the mystical Jewish tradition of the kabbalah.

Well I hope today, on the anniversary of Sir Thomas Browne's birth and death (how Ouroboros-like is that) that this little essay convinces my reader of Browne's very real interest and understanding of the kabbalah. It is, however , because of his having interests in early modern science in tandem with topics such as the kabbalah, that Browne's place in European intellectual history remains ambiguous and paradoxical today !

Notes

[1] The 1711 Action Sales Catalogue was finally published in 1986 thanks to scholarship of the Yale University, American academic and Dean Emeritus of Yale University, J.S. Finch (to whom I enjoyed a correspondence with until his death).

[2] The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age Frances Yates pub. RKP 1979

[3] De Harmonia Mundi Venice 1525 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue page 2 no.33

[4] P.E. Bk 1 chapter 3

[5] P.E. Bk 1 chapter 4

[6] Wikipedia

[7] P.E. Book 6 chapter 11

[8] Alchemy of the Word: Cabala of the Renaissance Philip Beitchman pub. State University of New York Press, Albany 1989

[9] Genesis 27 verse 15 discusses the adding of H to Abram's name.

Text here in chapter 5 includes a reference by Browne to - Archang. Dog. Cabal. Archangelus Burgonovus (The apology of brother Archangulus of Burgonovo in defense of cabalistic doctrines against Rev. Peter Garzia’s attack on Mirandula from Hebrew wisdom, source of the Christian religion). Basel 1560, Bologna 1564. Also mentioned in Pistorius’s Artis cabalisticae scriptores Basel 1587

[10] 1 Samuel 17 verse 40

With thanks to Karmel Lee for her encouragement.

Text here in chapter 5 includes a reference by Browne to - Archang. Dog. Cabal. Archangelus Burgonovus (The apology of brother Archangulus of Burgonovo in defense of cabalistic doctrines against Rev. Peter Garzia’s attack on Mirandula from Hebrew wisdom, source of the Christian religion). Basel 1560, Bologna 1564. Also mentioned in Pistorius’s Artis cabalisticae scriptores Basel 1587

[10] 1 Samuel 17 verse 40

With thanks to Karmel Lee for her encouragement.