Born on May 18th 1919, Margot Fonteyn was one of the greatest ballerinas of the 20th century. In addition to her dedication and technical skills, Fonteyn had the good luck to be coached firstly by the Russian dancer and ballet teacher Serafina Astafieva (1876-1934) then through joining the Vic-Wells company directed by its visionary founder Ninette de Valois (1898-2001) at a time when British ballet itself developed and came of age.

Over the course of decades, Fonteyn, along with Irish-born Ninette de Valois, and choreographer Frederick Ashton (1904-88) established ballet as a popular and serious art-form for British audiences. It can even be said that the rapid development of ballet in Britain as an art-form from circa 1935-1960 was primarily through the talents of Fonteyn as prima ballerina , the high standards instilled in the Corps de ballet by company director de Valois and the 'in-house' choreographic skills of Frederick Ashton. These combined factors contributed towards making what was to become the Royal Ballet, a company equal in stature to long established Russian ballet companies such as the Bolshoi and Kirov.

Fonteyn joined Ninette de Valois's Vic-Wells company (later Sadler Wells, later still, the Royal Ballet) in 1935 when precociously young. She soon found herself selected by de Valois for the highly responsible role of prima ballerina of the Company.

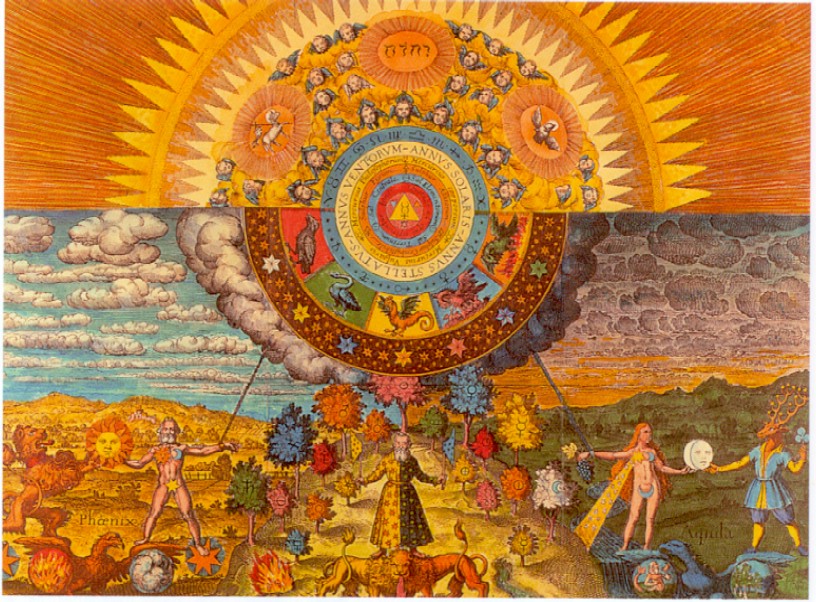

In her detailed biography of Fonteyn, author Meredith Danemann notes that it was also at this time that the ballerina had an on-and-off affair with the stage-conductor and composer Constant Lambert (1905-51). According to friends of Fonteyn, Lambert was the great love of her life and she despaired when she finally realised he would never marry her. Aspects of this relationship were symbolised in Lambert's astrologically-themed ballet Horoscope which was first performed on January 27th 1938. Tragically, Lambert was to die of alcoholism in 1951, only six weeks after his ballet Tiresias with its violent, sexual storyline had received hostile, damning reviews. Lambert's friends claim it was these reviews which led to the composer drinking even harder, effectively destroying himself at the age of 45.

Margot Fonteyn endeared herself to the British public by performing throughout the Blitz of the war-years. Undaunted by bombs, she refused to evacuate to a safer location and instead catered for the growing demand for ballet during the war, performing sometimes four or five times in a single day. After the war Fonteyn and the Sadler Wells Ballet company enjoyed worldwide fame following a rapturous reception in New York in 1949. They subsequently toured Australia to equally rave reviews. In 1956 Sadlers Wells was granted a Royal Charter by Queen Elizabeth II and became the Royal Ballet.

|

| Fonteyn and Robert Helpmann in 'Sleeping Beauty' (1946) |

In 1962 at an age when most ballerinas would be considering retirement, Fonteyn embarked upon a second career, partnering the charismatic dancer Rudolf Nureyev (1938-93) who had recently defected from the USSR. The ever-astute De Valois describes her first impressions of Nureyev during his curtain-calls after his first performance in London in 1961 thus-

'I saw an arm raised with a noble dignity, a hand expressively extended with that restrained discipline which is the product of great traditional schooling. Slowly the head turned from one side of the theatre to the other, and the Slav bone-structure of the face, so beautifully modelled, made me feel like an inspired sculptor rather than the director of the Royal Ballet. I could see him clearly and suddenly in one role - Albrecht in Giselle. Then and there I decided that when he first danced for us it must be with Fonteyn in that ballet', [1]

Others wrote more dramatically of Nureyev's performance, one dance critic stating it, 'produced the shock of seeing a wild animal let loose in a drawing-room'. [2]

In her book 'Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet' Judith Holman assesses Fonteyn and Nureyev's relationship and the reception of their first performance together in Giselle on 21 February 1962 thus-

'I saw an arm raised with a noble dignity, a hand expressively extended with that restrained discipline which is the product of great traditional schooling. Slowly the head turned from one side of the theatre to the other, and the Slav bone-structure of the face, so beautifully modelled, made me feel like an inspired sculptor rather than the director of the Royal Ballet. I could see him clearly and suddenly in one role - Albrecht in Giselle. Then and there I decided that when he first danced for us it must be with Fonteyn in that ballet', [1]

Others wrote more dramatically of Nureyev's performance, one dance critic stating it, 'produced the shock of seeing a wild animal let loose in a drawing-room'. [2]

In her book 'Apollo's Angels: A History of Ballet' Judith Holman assesses Fonteyn and Nureyev's relationship and the reception of their first performance together in Giselle on 21 February 1962 thus-

'At first glance, they seemed unlikely match: he was twenty-four and had a sweeping Soviet style, while she was forty-three and the paragon of English restraint. Yet together they created a potent mix of sex and celebrity that made them icons of the 1960s and "swinging" London's permissive scene:... It was pure populism, ballet for the youth generation and a mass consumer age,.. Fonteyn and Nureyev fashioned themselves into balletic rock superstars.

'How did they do it? The onstage chemistry between them has often been explained by sex: that they had it, wanted it, or suppressed it (they never told). But their partnership also stood for something much larger. In their dancing, East meets West: his campy sexuality and eroticism (heavy makeup with teased and lacquered hair) highlighted and offset her impeccable bourgeois taste. Nureyev played his role to perfection: even in the most classical of steps, he flirted with the image of the Asian potentate, and his unrestrained sensuality and tiger-like movements recalled a cliched Russian orientalism (first exploited by Diaghilev's Ballets Russe), which also linked to the escapist fantasies of 1960s middle-class youth: Eastern mysticism, revolution, sex, and drugs.

'The East was one thing; age was another. Nureyev had a gorgeous, youthful physique; Fonteyn was old enough to be his mother. And although her technique was still impressive, she looked her age. Indeed, as Fonteyn's proper 1950s woman fell into the arms of Nureyev's mod man, the generation gap seemed momentarily to close. .. Not everyone was happy with the result: the prominent American critic John Martin lamented that Fonteyn had gone "to the grand ball with a gigolo". None of this meant , however that Nureyev was disrespectful. To the contrary, when he partnered Fonteyn he did so with supreme respect and perfect nineteenth century manners. To the British, this mattered: Fonteyn, after all, was still "like the Queen" and during the curtain-call of their first performance of Giselle, Nureyev accepted a rose from Fonteyn and then instinctively fell to his knee at her feet and covered her hand with kisses. The audience went wild'. [3]

Fonteyn spoke of Nureyev's gesture after their first performance together thus-

'It was his way of expressing genuine feelings, untainted by conventional words. Thereafter, a strange attachment formed between us which we have never been able to explain satisfactorily, and which, in a way, one could describe as a deep affection, or love, especially if one believes that love has many forms and degrees. But the fact remains that Rudolf was desperately in love with someone else at the time, and, for me, Tito is always the one with black eyes'. [4]

More objectively, one dance-critic succinctly noted of the relationship -

'One unforeseen result of Nureyev's advent was a new lease of life for Fonteyn. Since Ulanova's retirement, she and Maya Plisetskaya of the Bolshoi shone above all rivals, but now there were sall signs of a possible end to her supremacy through declining technique and confidence. Nureyev changed all that. Responding to his highly charged stage presence, Fonteyn found a dramatic power that had previously eluded her. In place of the formerly reserved, carefully balanced dancer emerged a woman who threw herself impetuously into her roles. Consequently, she went on to many more years of recognition as a unique artist. [5]

'It was his way of expressing genuine feelings, untainted by conventional words. Thereafter, a strange attachment formed between us which we have never been able to explain satisfactorily, and which, in a way, one could describe as a deep affection, or love, especially if one believes that love has many forms and degrees. But the fact remains that Rudolf was desperately in love with someone else at the time, and, for me, Tito is always the one with black eyes'. [4]

More objectively, one dance-critic succinctly noted of the relationship -

'One unforeseen result of Nureyev's advent was a new lease of life for Fonteyn. Since Ulanova's retirement, she and Maya Plisetskaya of the Bolshoi shone above all rivals, but now there were sall signs of a possible end to her supremacy through declining technique and confidence. Nureyev changed all that. Responding to his highly charged stage presence, Fonteyn found a dramatic power that had previously eluded her. In place of the formerly reserved, carefully balanced dancer emerged a woman who threw herself impetuously into her roles. Consequently, she went on to many more years of recognition as a unique artist. [5]

Much has been written and speculated upon Fonteyn and Nureyev's relationship on and off-stage, Rudolf Nureyev is recorded as saying of Fonteyn - 'At the end of Lac des Cygnes (Swan Lake) when she left the stage in her great white tutu I would have followed her to the end of the world'. Nureyev later embarked upon a successful career as the director of the Paris Opera Ballet where he continued to dance and to promote younger dancers. He held this appointment as chief choreographer until 1989. Nureyev tested positive for HIV in 1984 and died tragically young from an AIDs related illness in 1993 aged just 54.

Equally tragic, Fonteyn's husband Tito was shot during an assassination attempt in 1964 resulting in his becoming a quadriplegic, requiring nursing for the remainder of his life. In 1972, Fonteyn went into semi-retirement, although she continued to occasionally dance until late in her life, partly through a need to subsidise her paraplegic husband's medical bills.

In 1979, as a gift for her 60th birthday, Fonteyn was fêted by the Royal Ballet and officially pronounced the prima ballerina assoluta of the company. The title was sanctioned by Queen Elizabeth II as patron of the company. Dame Fonteyn retired to Panama, where she spent her time writing books, raising cattle, and caring for her husband. She died from ovarian cancer on February 21st 1991, exactly 29 years to the day after her premiere with Nureyev in Giselle.

The first global super-star ballerina, Margot Fonteyn placed English ballet on the world-stage. She remains inspirational to dancers and loved by balletomanes throughout the world, still alive in spirit, one hundred years old today.

* * * *

There is one role which Fonteyn identified with, the water-spirit Ondine, choreographed especially for her by Frederick Ashton. Princess Aurora in Tchaikovsky's The Sleeping Beauty is another role she made her own. The 'Rose Adagio' in The Sleeping Beauty in which the ballerina remains balanced en pointe whilst receiving a rose from four suitors is considered to be a formidable technical achievement for a ballerina.

Notes

Some of Fonteyn's greatest roles were filmed. Mostly inexpensive on DVD, they also reflect the technology of the era, filmed over half a century ago; nevertheless they remain valuable records of Fonteyn as a ballerina.

* Swan Lake - Fonteyn and Nureyev Philips 1966

* The Royal Ballet - Firebird (Fokine) and Ondine (Ashton) 1960 Network DVD

* Kenneth MacMillan's Romeo and Juliet 1966 Network DVD.

Grainy colouration

* Sleeping Beauty 1955 VAI b/w

Recommended Books

pub. Viking 2004 654pp.

pub. Granta Books 2010 643pp.

* Invitation to the Ballet -Ninette de Valois

pub. Bodley Head 1937

Footnotes

[1] Ninette de Valois - Step by Step W. H. Allen 1977 cited by Daneman

[2] Alexander Bland Observer 5th November 1961 cited by Daneman

[3] Apollo's Angels- A History of Ballet-Jennifer Homans. Granta Books 2010

[4] Fonteyn Autobiography cited by Daneman

[5] Modern Ballet - John Percival pub. The Herbert Press 1970 rev. 1980

Documentary/Biopic DVDs

* Fonteyn and Nureyev -The Perfect Partnership 1985

* Margot Fonteyn - A Portrait Arthaus 1989

* Margot - BBC 2009