Earlier this

year I was introduced, courtesy of a friend, to the music of Osvaldo Golijov (b. 1960). The music of Golijov, who was born and grew up in Argentinia of East European and Judaic

descent, draws upon a wide spectrum including experimental

and electronic, Jazz and Pop, Klezmer music, the Tango and the folk traditions of World music. In addition to these varied musical influences Golijov has been well-qualified to absorbing world-wide music languages in his career. He moved from Argentina to Israel in 1983 to study music at the Rubin Academy at Jerusalem. In 1986 he relocated to America where he has taught music at the College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, Massachusetts since 1991.

The music-making of the Latin-American world, the city of Jerusalem and medieval Spain are of special inspirational value to Golijov. Each of these locations were once seminal places at the crossroads of overlapping cultures, where Christian, Muslim and Jew once peacefully co-existed.

I was probably

in a highly-charged emotional state last winter anyway when first hearing the

electrifying incantation by singer Dawn Upshaw which opens Ayre (2004). Golijov's song-cycle was influenced by a

creative urge to create a companion work

to Luciano Berio’s Folk Songs (1964) which draws upon traditional melodies from

America , Armenia ,

Sicily , Genoa ,

Sardinia, the Auvergne and Azerbaijan .

Golijov’s song cycle is no less eclectic and diverse than Berio's. It features the music of southern Spain and the

intermingling of Christian, Arab and Jewish cultures with texts from the Sephardic, Arabic, Hebrew and Sardinian

languages.

The influence of Berio’s

folk-song cycle is most evident in the gentle and traditional Sephardic song

which follows the incandescent opening. The next song Tancas serradas a muru in stark contrast is defiant and aggressive, near punk and urban rap-like in style, comes as a complete shock to those who imagine the performing persona of classically-trained singer Dawn Upshaw to be confined to the demure. Her reciting of Be a string, water, to my

guitar a calm, reflective, unaccompanied poem is insightful, while the song Yah , annah emtza’cha, aurally and vividly depicts the era of medieval Spain in which

Muslim, Jewish and Christian cultures once lived harmoniously. Golijov explains why Medieval Spain and the era of peaceful inter-relationship of religious faiths is close to his heart when commenting upon his song-cycle-

'With a little

bend, a melody goes from Jewish to Arab to Christian. How connected these

cultures are and how terrible it is when they don’t understand each. The grief

that we are living in the world today has already happened for centuries but

somehow harmony was possible between

these civilizations’

The song-cycle Ayre is one of several Golijov

compositions written specifically with the qualities and

interpretative insight of the mezzo-soprano Dawn Upshaw and her gorgeous singing voice in

mind. The subject of the strengths and weaknesses of composers writing with specific voices in

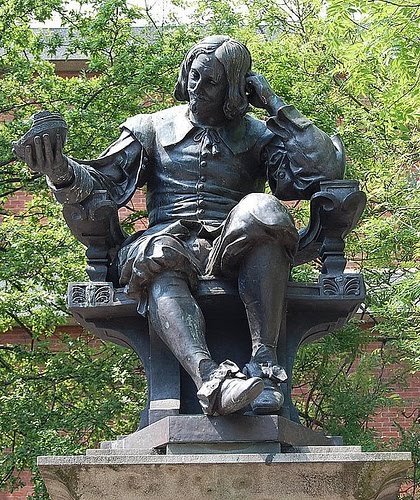

mind may well re-surface in musical discussion next year when the centenary of the

British composer Benjamin Britten (b.Lowestoft 1913) occurs. Britten wrote many song-cycles and opera parts specifically with the voice of his longtime partner the tenor Peter Pear in mind. Whether or not vocal works written for one specific voice in performance

and interpretation can be completely replicated by another, remains an open question.

Dawn Upshaw’s

recording of the song-cycle Ayre

concludes evoking Greek mythology with the tale of Ariadne in the labyrinth, a tense, mysterious and coiling musical theme

which highlights the instrumental

playing of the chamber ensemble, the Andalucian Dogs, as it slowly

fades into silence. Golijov’s final song in the cycle perfectly highlights the cross-fertilization of musical cultures within the Mediterranean

basin far better than words ever can. Golijov himself spoke of the creative

motivation of composing his song-cycle-

The idea is to

create a forest and for Dawn to walk in it. There is no real sense of ‘form’ –in

the sense of Beethovian development – but rather lots of detours and

discoveries’.

The title alone

of the opera Ainadamar (Arabic: Fountain

of Tears) appealed to me as the next work by Golijov work worth hearing. The opera’s title alludes to an

ancient well near Granada in Spain where the

poet Federico Garcia Lorca was murdered by Spanish Fascists in August 1936. First performed at the Tanglewood Festival in August 2003 Ainadamar is primarily based upon traditional Spanish music, in particular the Flamenco style. Once more the hypnotic voice of Dawn Upshaw is featured, this

time performing as Margarita Xirgu, a Catalan tragedian and Lorca's lover and muse, who collaborated with him on several of his plays. Without wanting to post spoilers there's a very startling moment in Golijov's opera about Garcia Lorca’s murder. In recent times the terror and trauma of

the Spanish civil war is the backdrop for film-director Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) a harrowing account of an episode in

the Spanish civil war interlinked with a fantasy world of magical

realism.