Its only in recent times that a clearer assessment of the Belgian chemist and scientist, physician and alchemystical philosopher Jan Baptist van Helmont (1579-1644) in science and medicine has been made. Likewise, its only recently that the influence of J.B.van Helmont on the English physician-philosopher Sir Thomas Browne (1605-82) has been recognised.

Just as historians only slowly acknowledged the seminal influence which the Swiss alchemist-physician Paracelsus (1493-1541) exerted upon the development of medicine during the Renaissance, so too, J. B. van Helmont has long occupied an ambiguous place in intellectual history.

J.B. van Helmont's writings are couched in the language of Renaissance mysticism and his belief in alchemy and magic is in tandem to his rational, scientific enquiries. This has resulted in an unsympathetic attitude towards him by historians of science and his writings labelled as an 'un-scientific' miscellany of medicine, philosophy and alchemy. One leading historian of medicine somewhat resignedly calling him an enigmatic figure.[1]

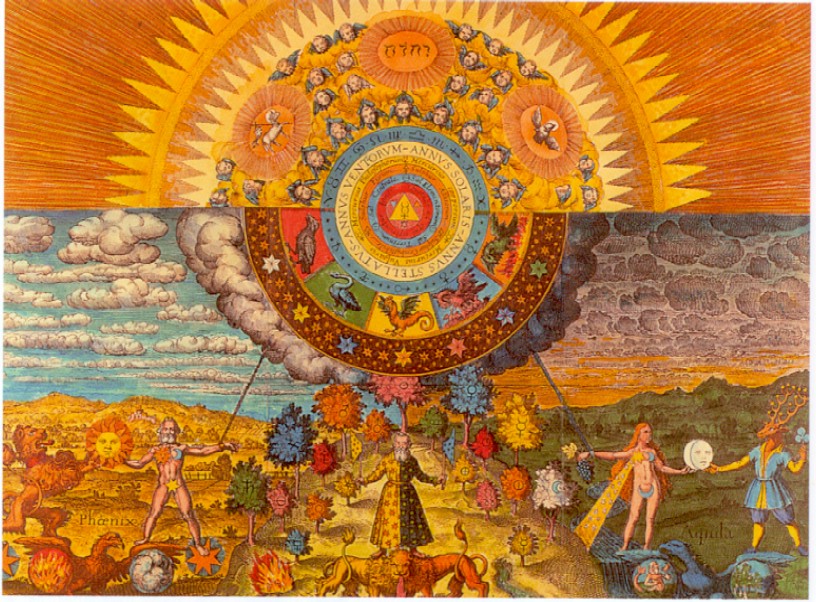

Quite simply the enigma of J.B. van Helmont rests in the paradox to modern sensibilities of his being defined in near equal measure as much a scientist and physician as religious mystic and 'alchemystical' philosopher. All these compartmentalized definitions did not of course exist in J.B. Helmont's time; himself possessing an entirely holistic and unified view of science, religion, medicine and philosophy.

Throughout his life J.B. van Helmont endured much misfortune. In his youth he gallantly picked up a glove which a lady had dropped only to be infected by scabies from it. He consulted the writings of the famous physician Galen for a remedy but found it ineffective and a sulphur ointment prescription by Paracelsus successful. He subsequently vowed to reject Galenic medicine and follow Paracelsus instead. J.B.van Helmont toured Europe, including London and worked in Antwerp during a plague epidemic in 1605. He graduated as Doctor of Medicine of the University of Louvain in 1599 but he was later denounced by his Alma Mater in 1623 as a heretic through the Spanish authorities occupying Flanders. His unorthodox views resulted in his arrest, trial and imprisonment in 1634 followed by house-arrest for the rest of his life. He almost died from Carbon monoxide poisoning in 1643 and contracted pleurisy in 1644. His good fortune however was to marry an heiress whose wealth enabled him to abandon his onerous medical duties and engage in scientific research for several years.

In essence, J.B. van Helmont is a transitional figure in the history of science. Like many other early scientists including Browne, he regarded all science and wisdom to be a gift from God. J.B. Helmont was also highly influenced by the so-called 'Luther of Medicine' in his scientific thought and experiments. It was the Swiss alchemist-physician Paracelsus who proposed that the true purpose of alchemy was to investigate the properties of nature, advocating the 'art of fire' to distil 'quintessences' of mineral and vegetable-life in order to discover new medicines. J.B. Helmont has been defined as the foremost follower of Paracelsus, who, whilst highly critical of Paracelsian mysticism nevertheless subscribed to what the Swiss physician termed his 'Spagyric' medicine, the rudimentary beginnings of iatrochemistry or medical chemistry no less, and as such J.B. van Helmont is credited, alongside the English scientist Robert Boyle (1627-91) as a 'Father of modern chemistry'.

Upon J.B. van Helmont's death in 1644 his son Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont (1614-98/99) randomly collated and edited his father's writings for the publication of Ortus Medicinae, or the 'Dawn of Medicine' in Amsterdam in 1648. An English translation by John Chandler entitled Oriatrike was published in London in 1662.

In his brilliant and scholarly biographical study of Thomas Browne, the American academic Reid Barbour notes Browne is especially keen to include J.B.van Helmont's research on magnetism in the forthcoming second edition of his Pseudodoxia Epidemica in 1650. [2] Other recent publications on Browne singularly fail to even mention J.B. van Helmont yet alone elaborate on his influence on Browne. However, scattered throughout his writings are several references to J.B. van Helmont which strongly suggest that the Norwich-based scientist and physician Thomas Browne held the Belgian scientist and physician in high regard. It shouldn't be too surprising to discover that Browne took the medical ideas of J.B. van Helmont seriously. Circa 1629 he had completed his continental studies at Leiden University in Holland, an educational institute whose reputation for chemical medicine was centred upon J.B. van Helmont's Paracelsian science.

Although none of J.B. van Helmont's writings are listed in the 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue of Browne's library (there's a lapse of almost 30 years from Browne's death until his library contents are auctioned. Not a single one of the books advertised on the Auction Catalogue title-page as 'Books of Sculpture and Painting' ever arrived at the auction-house) Thomas Browne surely had access to Van Helmont's writings. For example, when speculating on the formation of kidney-stones, a disease long prevalent in East Anglia due to its many chalky water-courses, Browne praises Van Helmont, albeit in parenthesis - '(as Helmont excellently declareth)'.[3] However, like J.B. van Helmont, Browne was also prone to read the 'Book of Nature' through the prism of esoteric schemata, the most elaborate being the microcosm-macrocosm correspondence, or from long-held folk-lore, as here-

'and Helmont affirmeth he could never find the spider and the fly upon the same trees, that is the signs of war and pestilence which often go together' [4]

Because early scientists such as Paracelsus, J.B. van Helmont and Thomas Browne encountered undefinable properties and phenomena in their scientific investigations they each had a propensity for coining and introducing new words, some of which remain in modern language. The word 'alcohol' is credited as originating from Paracelsus and that of 'electricity', amongst hundreds of others, to Browne. J.B.van Helmont's most famous neologism is undoubtedly the word 'gas' derived from the ancient Greek word for chaos. In fact, Van Helmont investigated and categorized a number of gases, including gas from belching, poisonous red gas (NO2) which is formed when aqua fortis (HNO3) acts on silver and sulfurous gas that “flies off” burning sulfur, amongst others. J.B. van Helmont proposed that gas is composed of invisible atoms which can come together by intense cold and condense to minute liquid drops; and that gases can be contained in bodies in fixed form, and set free again by heat, fermentation, or chemical reaction. In relation to combustion, he concluded there were two classes of gas which he named as Gas sylvestre – one that would not burn or support combustion (Carbon Monoxide) and Gas pingue – one that would burn (a combustible gas).

"That all plants immediately and substantially stem from the element water alone I have learned from the following experiment. I took an earthen vessel in which I placed two hundred pounds of earth dried in an oven, and watered with rain water. I planted in it a willow tree weighing five pounds. Five years later it had developed a tree weighing one hundred and sixty-nine pounds and about three ounces. Nothing but rain (or distilled water) had been added. The large vessel was placed in earth and covered by an iron lid with a tin-surface that was pierced with many holes. I have not weighed the leaves that came off in the four autumn seasons. Finally I dried the earth in the vessel again and found the same two hundred pounds of it diminished by about two ounces. Hence one hundred and sixty-four pounds of wood, bark and roots had come up from water alone".

Helmont's famous experiment was known to Thomas Browne. He alludes to it when speculating on water's ability to generate growth in The Garden of Cyrus-

'How water it self is able to maintain the growth of Vegetables, and without extinction of their generative or medical vertues; Beside the experiment of Helmont's tree, we have found in some which have lived six years in glasses'.

J.B van Helmont is only one of three 'moderns' who make the cut as worthy of mention in The Garden of Cyrus, the other two 'moderns' who also held in equal measure a rational and mystical view of science named in the discourse are the Swiss alchemist-physician Paracelsus (1493-1541) and the Italian esoteric scholar and polymath Giambattista Della Porta (1535-1615).

It was from Paracelsus that J.B. van Helmont evolved his own idea of an 'Archeus' or 'Master Workman' responsible for giving life and form to the human body. In Ortus Medicinae he situated the “archeus” in the upper opening of the stomach. All diseases according to J.B. van Helmont have their seat in the Archeus and every disease, he believed, had a vital principle of it own (archeus) which could be treated by a specific medical-spiritual response. Disease, J.B. van Helmont believed, could be overcome by pacifying the disturbed Archeus. Medicines, in particular, minerals, targeted the disease and helped the host overcome its archeus. According to J.B. van Helmont-

'A Disease therefore is a certain Being, bred, after that a certain hurtful strange power hath violated the vital Beginning...and by piercing hath stirred up the Archeus unto Indignation, Fury and Fear'.[5]

'Fever is the effort of the chief Archeus to get rid of some irritant, just as local inflammation is the reaction of the local Archeus to some injury'.[6]

J.B.Helmont's contemporary, the Paracelsian physician and alchemist Martin Ruland the Younger (1569-1611) attempts to define the nebulous term 'Archeus' in his Lexicon alchemiae (1612) thus-

ARCHEUS - is a most high, exalted, and invisible spirit, which is separated from bodies, is exalted, and ascends; it is the occult virtue of Nature, universal in all things, the artificer, the healer. Also Archiatros - supreme physician of Nature, who to every substance and member dispenses in an occult manner, by means of the air, its own individual Archeus. Also the primal Archeus in Nature is a most secret virtue producing all things out of Master, doubtless certainly supported by divine virtue. Or, Archeos is an errant, invisible species, the power and virtue of Nature's healing, the artist and healer of Nature, separating itself from bodies, and ascending from them. Archeus signifies, in addition, the power which reduces the One Substance from Iliaster, and is the dispenser and composer of all things. It individualizes in all things, including human nature.[7]

The medical ideas of J.B.van Helmont are linked to those of Thomas Browne in an astounding observation by the psychologist C.G. Jung (1875-1961). Writing on the Belgian alchemist Gerard Dorn, Jung unites the Paracelsian/ Helmontian concept of the Archeus with Thomas Browne's medical image of an 'invisible sun' which blazes at the apotheosis of Urn-Burial ('Life is a pure flame and we live by an invisible sun within us'.) C.G.Jung links Gerard Dorn, the foremost promoter of Paracelsian/Helmontian medicine to Thomas Browne's 'invisible sun' (an image Browne 'borrowed from his reading of Dorn) when stating-

In Dorn's view there is in man an 'invisible sun', which he identifies with the Archeus. This sun is identical with the 'sun in the earth'. The invisible sun enkindles an elemental fire which consumes man's substance and reduces his body to the prima materia. [8]

As a child J.B. Helmont experienced apocalyptic visions in the cloisters of the Capuchins at Louvain. Devout and pious throughout his life, he was deeply inspired by Thomas a Kempis (1380-1471) and his Imitation of Christ which urges the penitent to self-knowledge and a denial of the self for Christ.

The psychological element is ever-present in spiritual affairs, and in conjunction with his physiological studies J.B. van Helmont took the workings of the human psyche seriously. Indeed, J.B. Helmont may be credited as an Ur-psychologist, that is, any one of a number of well-educated and isolated individuals, often from the professions of physician or priest, scattered throughout Europe circa 1500-1700 who recognised a correct understanding and interpretation of one's personal dreams to be no small contributing factor towards self-awareness and individuation. To the present-day this spiritual-psychological dimension remains of paramount importance, in particular, not only for individual understanding of the self but equally, for the very future of humanity's existence. 'Alchemystical' physician-philosophers such as Paracelsus, J.B. van Helmont and Thomas Browne each engaged in the arduous yet rewarding task of self-realization, J.B. van Helmont declaring-

'Our soul's understanding of itself, does after a sort, understand all other things, because all other things are in an intellectual manner in the Soul, as in the image of God. Wherefore indeed, the understanding of ourselves, is most exceedingly difficult, ultimate or remote, excellent, profitable, beyond all other things'.[9]

J.B. Helmont was aware of the numinous nature of dreams. In the Judaic Pentateuch, the Old Testament of the Christian Bible, dreams are sanctioned as conduits of revelation from God. The story in the book of Genesis of Joseph and his ability to interpret Pharaoh's dreams was seen as endorsement of divine dreams and the art of interpretation. Using theological symbolism J.B. van Helmont seems to anticipate, along with other Renaissance-era alchemystical philosophers and Ur-psychologists, the existence of the unconscious psyche and its relationship to God when stating-

'In sleep, the whole knowledge of the Apple (i.e. that which obscures the magical powers of pristine man ) doth sometimes sleep: Hence also it is, that our dreams are sometimes Prophetical, and God himself is therefore the nearer unto Man in Dreams, through that effect'. [10]

In his writings J.B.van Helmont recollects a dream which determined his choice to become a physician. In this dream he saw himself as an empty bubble whose diameter reached from the earth to the heavens. Above the bubble hung a tomb, while below it was the dark abyss, a vision that horrified the young van Helmont. Upon waking he interpreted his dream and of being transformed into a giant bubble as representing his own boastful, vacuous self and a god-given sign that he must pursue the vocation of physician.

Thomas Browne was fascinated by dreams and was able to lucid dream, that is, able to orchestrate the events and action of a dream whilst in a state of dreaming, as he confesses in Religio Medici-

'Yet in one dream I can compose a whole comedy, behold the action, apprehend the jests and laugh myself awake at the conceits thereof. Were my memory as faithful as my reason is fruitful I would chose never to study but in my dreams". [11]

Browne even wrote a short tract On Dreams in which he speculates upon 'symbolical adaptation' in dream interpretation thus-

'Many dreams are made out by sagacious exposition and from the signature of their subjects; carrying their interpretation in their fundamental sense and mystery of similitude, whereby he that understands upon what natural fundamental every notional dependeth, may by symbolical adaption hold a ready way to read the characters of Morpheus'.

In his tract On Dreams Browne supplies his reader with examples of how dimensions can be greatly exaggerated in dreams, humorously exclaiming-

'Helmont might dream himself a bubble extending unto the eighth sphere'.

A statement which indicates Browne was familiar with J.B. Helmont's accounts of his mystical experiences as well as his medical and scientific thoughts. Browne himself took an interest in bubbles as seen in his short writing On Bubbles in which he proposes-

'Even man is a bubble if we take his consideration in his rudiments, and consider the vesicular or bulla pulsans wherein begins the rudiment of life.

Ever the subtle thinker, perhaps the strongest evidence of Thomas Browne's interest in J.B. Helmont's science occurs in correspondence to his travel-loving eldest son Edward Browne (1644-1708). Discreetly fishing for an answer Thomas Browne enquires-

'What esteem they have of Van Helmont, in Brabant, his home country ? [12]

In the same letter Thomas Browne also remarks-

'When you were at Amsterdam, I wished you had enquired after Dr.Helvetius who writ Vitulus aureus, and saw projection made, and had pieces of gold to show of it.' [13]

J.B. van Helmont himself believed in the existence of Philosopher's Stone and claimed he was once given it by a stranger writing- 'It was of a colour such as is saffron in it powder yet weighty and shining like unto powdered glass. ....He who first gave the the gold-making powder had likewise also at least as much of it as might be sufficient to change two hundred thousand pounds of gold. For he gave me perhaps half a grain of that powder, and nine ounces and three quarters of quicksilver were thereby transchanged. [14]

Late in his life Browne articulated his critical opinion and estimate of J.B. van Helmont and Paracelsus in his advisory and moralistic Christian Morals -

'many would be content that some would write like Helmont or Paracelsus; and be willing to endure the monstrosity of some opinions, for divers singular notions requiting such aberrations'. [15]

In other words, in Thomas Browne's view, the many original ideas which authors such as Helmont and Paracelsus express excuse them from 'monstrous opinions' which can be found elsewhere in their writings.

There remains one last remarkable connection between J.B. van Helmont and Thomas Browne, seldom, if ever noted before now. It exists in the form of the German translator, scholar of Hebrew and the kabbalah, Christian Knorr von Rosenroth (1636-1689). At the request of the kabbalist and wandering hermit Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont (1614-98/99) who had, together with Henry More of the Cambridge Platonists annotated Knorr von Rosenroth's translations of kabbalistic texts, Knorr von Rosenroth, in return for Franciscus van Helmont's favour, helped him translate, edit and publish into Latin his father J.B. van Helmont's writings.

|

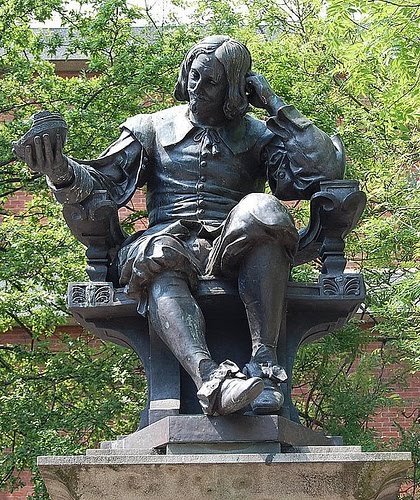

| Christian Knorr von Rosenroth (1636-89) |

In his relatively short life Christian Knorr von Rosenroth somehow found time to also translate Thomas Browne's vast-ranging work of scientific journalism, Pseudodoxia Epidemica totalling over 200,000 words into German, completing this task in 1680 for publication in Frankfurt and Leipzig. Its therefore quite possible that discussion of Thomas Browne's scientific writings could have occurred between Knorr von Rosenroth and J.B. Helmont's eldest son, Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont. A large field is yet to be explored in this matter.

In any event Christian Knorr von Rosenroth surely recognised J.B. van Helmont and Thomas Browne as sharing values in Paracelsian medicine and scientific thought. Indeed, the Belgian scientist, physician and Christian mystic J.B. Helmont may even lay claim to being along with Francis Bacon, one of the foremost scientific influences upon the physician-philosopher Thomas Browne.

Notes

[1] Roy Porter 'The Greatest benefit to Mankind': A medical history of humanity from antiquity to the present. pub. Harper Collins 1999 describes Helmont as enigmatic.

[2] Reid Barbour - Sir Thomas Browne A Life

pub. Oxford University Press 2013

[3] Pseudodoxia Epidemica Book 2 chapter 4

[4] P.E. Bk. 2 chapter 7

[5] Johannes Baptista van Helmont- Alchemist, physician and philosopher by H. Stanley Redgrove pub. William Rider and son London 1922

[6] Ibid.

[7] Martin Ruland's Dictionary of alchemy is listed in the 1711 sales auction catalogue as once in Browne's library page 22. no 119

[8] Collected Works of C.G.Jung Volume 14:49

[9] Redgrove 1922

[10] Ibid.

[11] Religio Medici Part 2 Section 11

[12] Correspondence dated September 22nd 1668 to Edward Browne

[13] Ibid.

[14] The Devil's Doctor: Paracelsus and the World of Renaissance Magic and Science pub. Heinemann 2006 by Philip Ball

[15] Christian Morals Part 2 Section 5

Not consulted

The standard, comprehensive of J.B.Helmont, prohibitively priced is-

* Joan Baptista Van Helmont: Reformer of Science and Medicine (Cambridge Studies in the History of Medicine) Walter Pagel pib.Cambridge University Press 1982

But possibly the most modern interpretation of J.B. van Helmont yet is-

* An Alchemical Quest for Universal Knowledge: The 'Christian Philosophy' of Jan Baptist Van Helmont (Studies in Intellectual History, 1550-1700) Routledge 2016 by Georgiana D. Hedesan

See also -

* Paracelsus and Sir Thomas Browne

* Paracelsus and the interpretation of dreams

* Thomas Browne and the Kabbalah