The seductive figure of the mermaid has a fascinating place in world art and literature.

An early western literary account of the mermaid legend

occurs in a medieval Romance which tells of Melusine, a fairy of

extraordinary beauty who sometimes changes into a serpent. A popular fifteenth century Romance recounted the tale

of Melusine, a fairy who promises to marry Raimondin of Lusignan and make him a rich king if he agrees to marry but never to look at her on a Saturday evening. They marry and Raimondin grows wealthy, while Melusine with her magic builds him a castle. Raimondin however, is also consumed with

jealousy, suspecting his wife of unfaithfulness. One Saturday evening he gouges a spy-hole through a

wall to watch Melusine when she retires to her room. While she is bathing he sees that his wife

has become half woman, half serpent. Melusine, distressed at being seen transformed flies away with frightful screams. Associated through marriage with the Lusignan family, Melusine appears over the centuries on the towers of their castle, wailing mournfully every time a disaster or death in the

family is imminent.

In the utterly charming novel The

Wandering Unicorn (1965) by the Argentinian author Manuel Mujica Lainez (1910-64)

the legend of Melusine is developed further. Set in medieval France and the

holy Land of the Crusades, Lainez’s novel is a rich serving of fantasy and romance. Narrated from the perspective of

the shape-changing Melusine, the early events of the original legend are soon

recounted before she embarks upon an adventure and unrequited love-affair with

Aiol, the son of Ozil, a crusader knight who bequeaths a Unicorn’s lance to his

son. Together the young knight Aiol and

Melusine travel across Europe to eventually arrive in war-torn Jerusalem of the Crusades.

The reader is drawn into Lainez’s neglected gem of magical realism with

growing empathy towards Melusine as she recollects her adventures and love of Aiol, only to experience the full emotional impact of the tragic and sad ending of the love-affair between a mortal and an immortal.

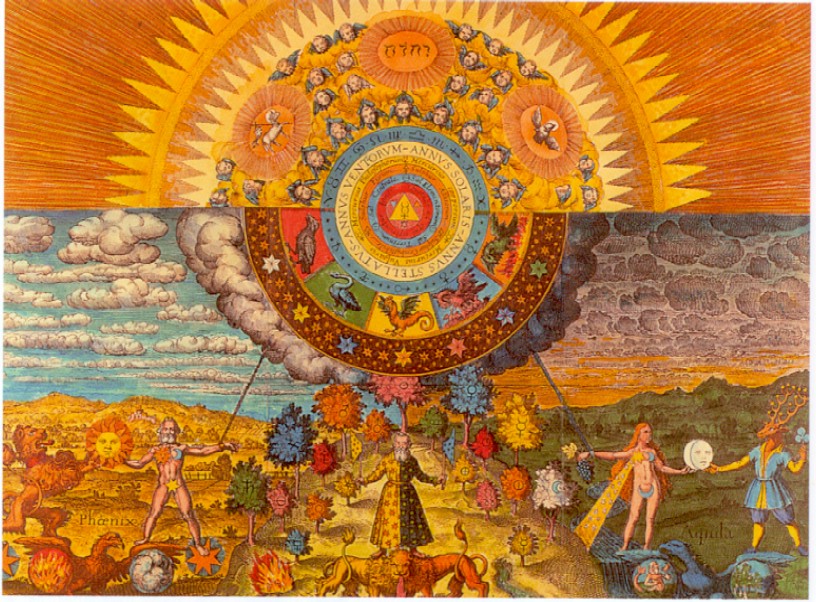

18th century Melusine with the four Elements

The Renaissance alchemist-physician

Paracelsus (1493-1541) also fell under the potent spell of the mermaid Melusine.

It’s worth remembering that Paracelsus, above all others, was the

foremost alchemist who influenced the psychologist C.G. Jung. Both men were physicians of Swiss-German nationality as well as radical protestant

theologians. In the darkest year of World War II, 1942 C.G. Jung delivered a conference paper on the Swiss physician at Zurich for the quatercentenary anniversary of Paracelsus's death in 1542, which analysed the symbolism of the mermaid, stating in his essay Paracelsus as a Spiritual Phenomenon -

Melusine comes into the same category as

the nymphs and sirens who dwell in the watery realms. In his De Pygmaeis Paracelsus informs us that

Melusina was originally a nymph who was seduced by Beelzebub into practising witchcraft. She was descended from the whale in whose belly the prophet Jonah

beheld great mysteries. This derivation is very important: the birthplace of

Melusina is the womb of mysteries, obviously what we today would call the

unconscious. Melusines have no genitals, a fact that characterizes them as paradisiacal

beings, since Adam and Eve in paradise had no genitals either……Adam and Eve

“fell for” the serpent and became “monstrous”, that is, that they acquired

genitals. But the Melusines remained in the paradisal state as water creatures

and went on living in the human blood. Since blood is a primitive symbol for

the soul, Melusina can be interpreted as a spirit, or some kind of psychic

phenomenon. Gerard Dorn confirms this in his commentary on De Vita longa , where he says that Melusina is a “vision appearing

in the mind.” For anyone familiar with the subliminal processes of psychic

transformation, Melusina is clearly an anima figure. She appears as a variant

of the mercurial serpent, which was sometimes represented in the form of a

snake-woman by way of expressing the monstrous, double nature of Mercurius.[1]

C.G. Jung defined the alchemists of the

medieval and Renaissance era as none other than embryonic psychologists who recognized the very real existence of the psyche but lacked a terminology to describe the psyche’s workings. According to Jung-

Paracelsus seems to have known nothing of

any psychological premises. He attributes the appearance and transformation of

Melusina to the effect of the “intervening” Scaiolae, the driving spiritual

forces emanating from the homo maximus.[2]

The four Scaiolae or spiritual powers of the mind of Paracelsian alchemy have a distinct affinity to C.G. Jung’s preciser four nominated functions of the psyche, namely, thinking, feeling, sensation and intuition. Jung defined the Paracelsian Scaiolae and their relationship to Melusina thus-

Since the Scaiolae are psychic functions….as functions of consciousness, and particularly as imaginato, speculation, phantasia and fides, they “intervene” and stimulate Melusina, the water-nixie, to change herself into human form….Now this figure is certainly not an allegorical chimera or a mere metaphor: she has her particular psychic reality in the sense that she is a glamorous apparition who, by her very nature, is on one side a psychic vision but also, on account of the psyche’s capacity for imaginative realization is a distinct objective entity, like a dream which temporarily becomes reality. The figure of Melusina is eminently suited to this purpose. The anima belongs to those borderline phenomena which chiefly occur in special psychic situations. [3]

In this context the anima figure's role in the individuation process is of great significance. Paracelsus apprehended this fact when identifying the 'difficult' nature of Melusine in her relationship to the Scaiolae of the homo maximus or the greater man within.

Illustration by Charles Robinson 1937

J. Jacobi in a glossary to selected works by Paracelsus, defines Melusina as -

A legendary, magic being, whose name Paracelsus also uses to designate an arcarnum. He conceives of it as a psychic force whose seat is a watery part of the blood, or as a kind of anima vegetativa (vegetative soul.)

In a fine example of how male fantasy invariably either under-values or over-values the anima figure (although often considered of a helpful, guiding nature there's also malevolent aspects of the femme fatale in the mermaid) and how Christian misogyny conspired to condemn the mermaid as symbolic of sinful sensuality, the Paracelsian scholar and lexiconographer, Martin Ruland in his Dictionary of Alchemy (1612) asserted -

Mermaids were Kings' daughters in France, snatched away by Satan because they were hopelessly sinful, and transformed into spectres horrible to behold...They are thought to exist with a rational soul, but a merely brute-like body, of a visionary kind, nourished by the elements and, like them, destined to pass away at the last day unless they contract a marriage with a man. Then the man himself may, perish by a natural death, while they live naturally by this nuptial union.

Invariably portrayed as solitary and beautiful with long-flowing hair, not easy to become acquainted with, changeable in mood and elusive, often fleeing from human presence when approached, with an ability to inhabit an alien element, namely water, the mermaid represents the archetype of the anima in Jungian psychology. The anima is born from unconscious contents associated with, and projected onto ‘the other’ which in the male psyche is the female sex, gender being the greatest divide of nature which includes human nature.

C.G.Jung considered fish to be perfect symbols of the contents of the unconscious psyche and the element of water itself as a symbol of the unknown and therefore also of the unconscious psyche. In essence the mermaid is a composite symbol of alluring virgin attached to an alien and repellent fish-form. From this tension of opposites, half seductress, half fish, C.G.Jung recognised the mermaid as another symbol connected to the shape-shifting deity associated with reconciling the opposites in alchemy, Mercurius.

During the romantic era of the nineteenth century the mermaid became an object of sentimentality. Hans Christian Anderson’s fairy-tale The Little Mermaid (1837) inspired Carl Jacobsen, son of the founder of the Carlsberg brewery who had been entranced by a ballet he'd seen based upon Anderson’s fairytale at Copenhagen's Royal Theatre. In 1913 Jacobsen commissioned a bronze sculpture of a mermaid by Edward Ericksen which was placed in the entrance to Copenhagen harbour. Ericksen’s sculpture, though often sadly frequently vandalized, has become emblematic of the city of Copenhagen. The capital city of Warsaw in Poland has had a mermaid as part of its heraldic coat-of-arms since the 14th century.

Fascination with the slippery and wet fantasy of the mermaid became increasingly eroticized in paintings of the late romantic era. In British artist Frederic Leighton’s The Fisherman and the Siren (top picture) for example, the sheer unashamed erotic content of the mermaid is celebrated as in many other late 19th century paintings in which the mermaid is an object of male fantasy and elusive desire.

The mermaid could not possibly slip away into the sea of obscurity and escape from the sharp-eyed scrutiny of the 17th century British scholar of comparative religion Sir Thomas Browne. In his encyclopaedia Pseudodoxia Epidemica, he noted of the mermaid's resemblance in the ancient world to the winged siren, and to Dagon, an ancient Assyro-Babylonian fertility fish-god, noting-

Few eyes have escaped the Picture of Mermaids; that is, according to Horace his Monster, with woman’s head above, and fishy extremity below: and these are conceived to answer the shape of the ancient Syrens that attempted upon Ulysses. Which notwithstanding were of another description, containing no fishy composure, but made up of Man and Bird; ........

And therefore these pieces so common among us, do rather derive their original, or are indeed the very descriptions of Dagon; which was made with human figure above, and fishy shape below; whose stump, or as Tremellius and our margin renders it, whose fishy part only remained, when the hands and upper part fell before the Ark. Of the shape of Atergates, or Derceto with the Phœniceans; in whose fishy and feminine mixture, as some conceive, were implyed the Moon and the Sea, or the Deity of the waters; and therefore, in their sacrifices, they made oblations of fishes. From whence were probably occasioned the pictures of Nereides and Tritons among the Grecians, and such as we read in Macrobius, to have been placed on the top of the Temple of Saturn. [4]

Japanese hentai anime of the anima figure of the Mermaid.

Notes

[1] C.G.Jung Collected Works vol. 13. 180

[2] Vol. 13:220

[3] Vol. 13:216-217

[4] Pseudodoxia Epidemica book 5 chapter 19

Posted for Emily Josephine Jackman on her birthday with love.