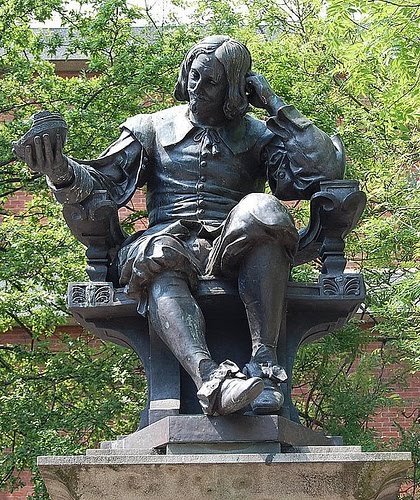

The Swiss physician and alchemist Paracelsus (1493-1541) has a fascinating, yet little explored relationship to the 17th century physician, hermetic philosopher, scientist and literary artist, Sir Thomas Browne.

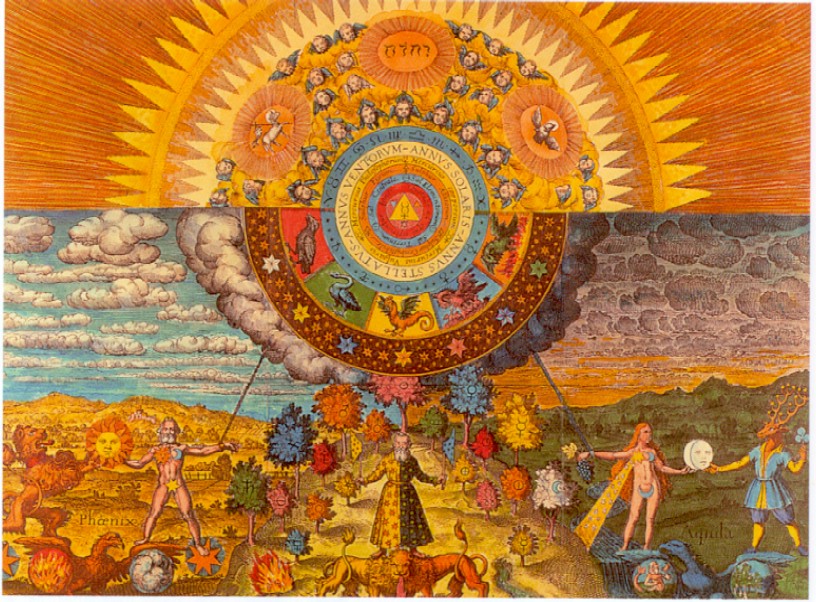

It’s only relatively recently in the light of modern understanding, notably by scholars such as Carl Jung, Frances Yates and Jean Seznec that the profound influence of hermetic and esoteric thought upon scientists, artists and physicians during the Renaissance has been recognized.

Following the early death of the 'German Hermes', as his advocates termed him, the writings of Paracelsus, a conglomerate of practical advice on how to develop new chemicals for medicine, mixed with proto-psychology and mystical theology attracted many followers. The new Spagyric medicine which Paracelsus taught during his short, wandering life, retained a potent influence upon alchemists, early scientists and in particular, physicians. Indeed, the radical physician has been called- "the precursor of chemical pharmacology and therapeutics and the most original medical thinker of the sixteenth century."[1]

The two favoured professions of would-be alchemist and hermetic philosopher alike were those of priest and physician. These two professions witnessed a wide spectrum of the human condition. Daily in contact with suffering and the inner spiritual man, priest and physician often worked in tandem, notably in attendance at the sick-bed. Indeed, the very title of Browne’s Religio Medici, (The Religion of a Doctor) is indicative of the intimate connection between the two vocations. It cannot be under-stated that as devout Christians, both Paracelsus and Browne shared a deep piety and viewed the healing of the sick as a religious duty. In Paracelsus’s own words - ‘Compassion is the physician's teacher’; while in his voluminous theological writings there can be found a theologian as original and free-thinking as his contemporary, Martin Luther.

In all probability Thomas Browne was introduced to Paracelsian literature during his student years when studying medicine either at the university of Padua, Montpelier or Leyden circa 1627-1630. Originally written upon completion of his medical studies, Religio Medici reveals its author as one well-acquainted with the ideas of Paracelsus.

Although objecting that –

‘the singularity of Paracelsus be intolerable reviled all learning before him’,

Browne nevertheless also confesses in Religio Medici to having- 'perus'd the Archidoxis and read the secret Sympathies of things' the Archidoxis being a treatise by Paracelsus on medical cures by means of magical properties attributed to gems and amulets. Likewise, although vehemently refuting Paracelsus' claim to have created a Homunculus, the fabled test-tube human of alchemy, declaring -

'I am not of Paracelsus mind that boldly delivers a receipt to make a man without conjunction' [2]

Browne nevertheless did believe in the Swiss physician's claim to have performed the alchemical feat of Palingenesis, that is, the revival of a plant from its ashes-

A plant or vegetable consumed to ashes, to a contemplative and school Philosopher seems utterly destroyed and the form to have taken his leave for ever. But to a sensible Artist the forms are not perished, but withdrawn into their incombustible part, where they lie secure from the action of that devouring element. This is made good by experience, which can from the ashes of a plant revive the plant, and from its cinders recall it into stalk and leaves again. [3]

The poet Coleridge, who was an early and enthusiastic reader of Browne, rose to his defence, annotating his personal copy of Religio Medici thus-

'This was, I believe, some lying Boast of Paracelsus, which the good Sir T. Browne has swallowed for a Truth'. [4]

An even greater number of statements on Paracelsus can be found in Browne's encyclopaedic endeavour Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646-1672). In an early example of scientific journalism, Browne revised each of the six editions of his best-selling encyclopaedia in his life-time, duly up-dating reports of his 'elaboratory' experiments, for example -

It is not suddenly to be received what Paracelsus affirmeth, that if a Loadstone be anointed with Mercurial oil, or only put into Quicksilver, it omitteth its attraction for ever. For we have found that Loadstones and touched Needles which have laid long time in Quicksilver have not amitted their attraction. And we also find that red hot Needles or wires extinguished in Quicksilver, do yet acquire a verticity according to the Laws of position in extinction.[5]

Although in Pseudodoxia Epidemica Browne debunks Paracelsus’s fervid quest for the Philosopher’s Stone –

More veniable is a dependence upon the Philosophers stone, potable gold, or any of those Arcana's whereby Paracelsus that died himself at forty seven, gloried that he could make other men immortal. [6]

when writing on the mythical creature the Phoenix, he reveals himself to be well-acquainted with Paracelsus and esoteric literature in general-

Some have written mystically, as Paracelsus in his Book De Azoth, or De ligno & linea vitæ; and as several Hermetical Philosophers, involving therein the secret of their Elixir, and enigmatically expressing the nature of their great work [7]

Strong evidence of Browne's own adherence to the goals of alchemy occurs in the so-called 'Alphabetical Table' to Pseudodoxia Epidemica which includes the index entry - 'Philosophers Stone, not impossible to be procured' a statement which seems to be unequivocal evidence of Browne's cautious and critical, yet believing, approach to alchemy. [8]

It's from Paracelsus' interest in Austrian folk-lore that Browne wrote-

and wise men may think there is as much reality in the pygmies of Paracelsus; that is, his non-Adamical men, or middle natures betwixt men and spirits.[P. E. 4:11].

The Swiss alchemist-physician proposed that a particular spirit resided over each element. Nymphs ruled the water, the Salamander, fire, Sylphides, the air, and citing Germanic folk-lore, he claimed that deep in the earth there exists a race of dwarf- like Earth-spirits, which he named Gnomes. According to Paracelsus these little people were the guardians of the earth who knew where precious metals and hidden treasure were buried. The word gnome, another neologism of Paracelsus, originates from a play on the Greek words of gnomic meaning knowledge and intelligence and genomus meaning 'earth-dweller'. Paracelsus described Gnomes thus-

The gnomes have minds, but no souls, and so are incapable of spiritual development. They stand about two feet tall, but can expand themselves to huge size at will, and live in underground houses and palaces. Adapted to their element, they can breathe, see and move as easily underground as fish do in water. Gnomes have bodies of flesh and blood, they speak and reason, they eat and sleep and propagate their species, fall ill and die. They sometimes take a liking to a human being and enter his service, but are generally hostile to humans.

Browne concluded his speculation upon the existence of little people open-mindedly stating -

we shall not conclude impossibility, or that there might not be a race of Pygmies, as there is sometimes of Giants. [P. 4:11].

The first ever Gnome named in literature was Umbriel in Alexander Pope's poem The Rape of the Lock (1712). An eerie aural depiction of the Gnome can be heard in the Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky's suite Pictures at an Exhibition which was imaginatively orchestrated by the French composer Maurice Ravel.

Paracelsus, the self-styled 'Luther of Medicine' was an early advocate of opium in medicine. Throughout the history of alchemy a considerable knowledge of substances, minerals and drugs can be found. Widely in use since the sixteenth century, opium was used to relieve such disorders as dysentery and respiratory ailments. By the seventeenth century, physicians required a license in order to obtain Opium, the only available pain-killer and tranquillizer in medicine of the day. Such was its widespread usage in seventeenth century medicine that Browne's contemporary, Thomas Sydenham (1624-89) declared-

Among the remedies which has pleased the Almighty God to give to man to relieve his sufferings, none is so universal and so efficacious as opium.

In 1959, the critic Peter Green suggested that one reason why Browne's prose is stylistically unlike any of his contemporaries, may have been due to his experimenting with drugs. Green noted that the twin Discourses of 1658 were penned by a Royalist who was under intense emotional and psychological distress, and proposed that the last chapters of both Discourses were written in a trance-like condition. On several occasions in Urn-Burial Browne poetically links opium's effects with the theme of the unknowingness of the human condition such as-

The iniquity of oblivion blindly scattereth her Poppy.

while crucial evidence that he observed the psychological effects of opium can be found in his medical-philosophical declaration-

'There is no antidote for the Oblivion of Time which temporally considereth all things'

The phrase 'temporally considereth all things' is Browne's succinct observation of opium's psychological effects, whilst the moralist in him however denounced all trafficking in substances, sternly declaring later - 'Oblivion is not to be hired'.

Today there's strict legislation and laws on drug consumption, however, this was not so during the seventeenth century, which saw the foundation of addictions now long-standing in Western society with the widespread introduction and consumption of the newly-discovered tobacco-leaf and Coffee throughout Europe. Although it is difficult nowadays with our politically correct thinking to accept that a devout Christian and respected doctor may have written his 'deep, stately, majestic' prose (De Quincey) with its slow, sombre contemplations under the influence of Opium, for the empiricist, such as Browne, as for the alchemist, the self and the sensory impressions were the seat of all experiment. There are several notes upon the effects of dosages of narcotics in Browne's common-place books but whether his empirical nature endorsed experimenting with drugs it is not documented, however he may well have done so accidentally, or as part of his alchemical quest. It's also worth remembering that as a botanist with an interest in toxicology, Browne may well have been able to identify psilocybin and fly agaric fungi.

Whether or not Browne ever had his hand in the medicine-cabinet will never be known, however it’s certainly a big coincidence that his labyrinthine prose was 're-discovered' by the early Romantic figures of Coleridge and De Quincey, both of whom suffered from the ravages of drug-addiction at cost to their longevity and artistic productivity.

The 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue of Browne and his son Edward’s libraries, supplies further evidence that the ideas of the Swiss Renaissance physician were an influence upon the Norwich physician. Not only does it list an edition of the complete Opera of Paracelsus, but also many books by followers of spagyric medicine, including the chief protagonist of Paracelsian medicine, Gerard Dorn, as well as books by Alexander von Suchten, Theodore Turquet de Mayerne, Joseph Duchesne, Martin Ruland, Petrus Severinus and John French. In fact it would have been near impossible for any medical practitioner of the seventeenth century not to have had a strong view upon Paracelsus. England saw slower acceptance of what was perceived to be continental medicine. In any event such a number of books by medical advocates in Browne's library once again suggests more than a casual interest in Paracelsian medicine. [9]

Paracelsus was fond of inventing new words to describe his alchemical/astrological form of medicine. For example he described himself as a pagoyum a neologism composed from the combing the words "paganum" and the Hebrew word "goy". Similarly, Paracelsus described his type of medicine as an 'Yllaster' a word coined from plaster and astrum a star ; in this context its worthwhile looking at the verse inscribed upon the Coffin-plate of Sir Thomas Browne's lead Coffin.

It’s not known who composed the inscription verse upon Browne's Coffin-plate. It may have been written by Browne's eldest son Edward, one of the few people who really knew him well, or the author may have been Browne himself. But whether written by father or son, the fact remains that the Paracelsian word, spagyrici the name of Swiss alchemist-physician's distinctive brand of alchemy, is engraved upon Browne's coffin-plate. The word spagyrici is a typical Paracelsian neologism which is believed to derive from the fusing of the Greek words Spao, to tear open, and ageiro, to collect

Browne’s coffin-plate inscription alludes to the commonplace quest of alchemy, the transformation of metals which for the spiritual alchemist signified a far deeper goal - the transformation of the base matter of man to acquire spiritual gold –

Hoc locuolo dormiens, corporis spagyricci pulvere plumbum in aurum convertit

translated reads-

Sleeping here the dust of his spagyric body converts the lead to gold.

The usage of the Paracelsian word spagyrici meaning to tear apart and to bind, a polarised maxim not dissimilar to the commonplace maxim of alchemy solve et coagula is perhaps the strongest concrete evidence which refutes claims that Browne's interest in Paracelsian medicine was merely marginal.

Far from being opposed to Paracelsian medicine, all the evidence suggests, that like the German chemist Andreas Libavius (1564-1616) Browne possessed a thorough and critical knowledge of Paracelsian literature, in both its practical and mystical forms, and just like Libavius (who is approvingly alluded to by Browne in P.E.) he was a critical follower of Paracelsian medicine.

But perhaps of far the most important influence of Paracelsus upon Browne is that of the Swiss physician's usage of proper-names from mythology in order to describe the psyche and its components. Most striking of all is Paracelsus's choice of symbolic proper-names to represent the alchemical art, namely Vulcan, the Roman god of fire. A flavour of Paracelsian alchemy can be gleaned from this extract-

This process is alchemy; its founder is the smith Vulcan… And he who governs fire is Vulcan, even if he be a cook or a man who tends a stove….To release the remedy from the dross is the task of Vulcan…This is alchemy, and this is the office of Vulcan; he is the apothecary and chemist of the medicine. Everything is at first created in its prima materia, its original stuff; whereupon Vulcan comes, and by the art of alchemy develops it into its final substance….Alchemy is a necessary, indispensable art…It is an art and Vulcan is its artist. He who is a Vulcan has mastered this art; [10]

It can hardly be coincidental that the very opening sentence of Browne’s The Garden of Cyrus depicts the Roman god Vulcan as an alchemist of the Creation.

That Vulcan gave arrows unto Apollo and Diana the fourth day after their Nativities, according to Gentile Theology,may passe for no blinde apprehension of the Creation of the Sunne and Moon, in the work of the fourth day; When the diffused light contracted into Orbes, and shooting rayes, of those Luminaries.

The Roman god Vulcan, patron 'saint' of alchemists is named twice more in The Garden of Cyrus, crucially at the discourse's apotheosis in which Browne states his determinants for acquiring scientific certainty.

Flat and flexible truths are beat out by every hammer, but Vulcan and his whole forge sweat to work out Achilles his Armour.

Scattered, throughout both Urn-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus there can be found observations made from two of Browne's amateur pursuits, namely archaeology and botany which add empirical depth to the alchemical theme of the discourse's study of 'solve et coagula' or decay and growth; more importantly Browne's diptych discourses, not unlike passages of the Ur-Psychologie of Paracelsus, attempt to delineate components of the psyche. Indeed, not only does one of the very earliest usages of the word 'archetype' occur in The Garden of Cyrus but throughout the discourse highly original proper-name symbolism is employed to designate components or archetypes of the psyche.

In the twentieth century C. G. Jung held a deep interest in Paracelsus. The Swiss physician was well-aware of his earlier compatriot's importance in the history of the understanding of the psyche, an understanding which only began with a tentative recognition of the psyche itself, in writings by hermetic philosophers such as Paracelsus and Sir Thomas Browne. Jung's two essays on Paracelsus remain rewarding reading. Indeed, during the darkest hours of World War II in 1943 Jung calmly lectured upon Paracelsus in Zurich. Jung also shares with Browne a remarkably similar assessment of Paracelsus for while he described Paracelsus' writings as –

'long dreary stretches of utter nonsense (which) alternate with oases of inspired insight'.[11]

Browne, late in his life considered –

'many would be content that some would write like Helmont or Paracelsus; and be willing to endure the monstrosity of some opinions, for divers singular notions requiting such aberrations. [12]

Today, Jung’s assessment of the relevance of Paracelsus to our own time has become equally applicable to the growing interest in Sir Thomas Browne-

Paracelsus was, perhaps most deeply of all, an alchemical "philosopher" whose religious views involved him in an unconscious conflict with the Christian beliefs of his age in a way that seems to us inextricably confused. Nevertheless, in this confusion are to be found the beginnings of philosophical, psychological, and religious problems which are taking clearer shape in our own epoch.

Notes

[1] Manly Hall

[2] R.M. I: 36

[3] R.M. 2:35

[4] R.M. 1 :45

[5] P.E Bk 2 :3

[6] Bk 3:12

[7] Bk 3 :12

[8] 1658 edition in author's possession.

[9] 1711 Sales Catalogue

[10] Paracelsus - Selected Writings Jolande Jacobi pub. Princeton 1988

[11] C.W. 15

[12] Christian Morals 2:6