Recently I had the pleasure of an evening with the artist Peter Rodulfo. Modest and soft-spoken, Rodulfo is a gifted, prolific and visionary painter who is equally adept in portraiture as in fantasy as in landscape. His paintings are by turns graphic, witty and mystical.

While in conversation with the artist, over a bottle or two of wine, and in between reminiscing about 1970's

There’s more than a little of the rebellious and eccentric about Rodulfo who exhibits archetypal Aquarian characteristics in his personality and art. Reticent and even downright self-depreciating at times, a casual glance at his book-case reveals favourite authors such as Honore de Balzac, who was no mean occultist and physiognomist, and the autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections by the seminal psychologist C.G.Jung. Almost all the available wall space at his home is given to a kaleidoscopic gallery of his art, recent work and older personal favourites are all mixed together - Tolkienesque landscapes, animated portraiture of sharply-observed character and dream-like imagery jostle for the viewer's attention. Such a cornucopia of paintings gives a strong impression of a life-time's productivity and testimony to an industrious and disciplined creativity.

Although he’s travelled the globe, it’s the city of Norwich England , life moves at a Do Different pace. Many artists have

appreciated Norwich'

It’s easy for Rodulfo to give a nod to the art of Paul Klee, Max Ernst and De Chirico for example, while remaining very much his own man. Although his art utilizes some of the techniques and motifs associated with surrealism, as well as magical realism, he retains his artistic integrity. Labels are often misguiding and Rodulfo wisely eschews any eager and simplistic labelling of his still evolving creativity. But although comparisons can be misleading, there is one British artist whose art is worthy of note in both technique and imagination to Rodulfo's - that of the self-exiled British surrealist artist Leonora Carrington (1917-2011). Like Carrington, Rodolfo acknowledges the role the unconscious psyche plays in his creativity. Like Carrington, Rodulfo's symbolism is home-grown and capable of striking a deep chord in its unconscious association. Finally, like Carrington, Rodulfo is equally adept at draughting a layered field of perspective to showcase his artistic vision. His paintings, like the best surrealist or magical realist painters can be a vivid encounter with the unconscious psyche, or more correctly in Rodulfo's case, a polite enquiry into the viewer's relationship to their own unconscious psyche.

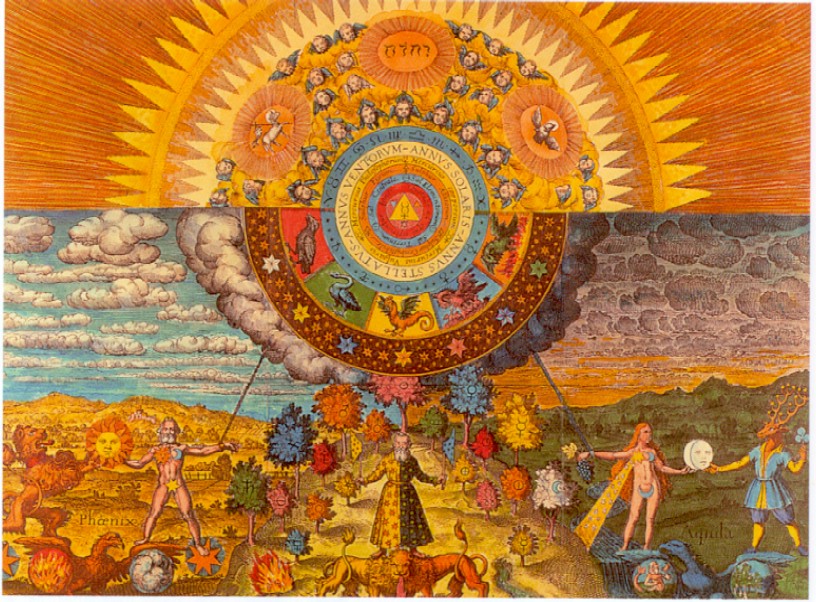

Rodulfo's canvas As the Elephant laughed (above) exhibits a rich vocabulary of symbolism evoking a panorama of life on earth. The relentless march of time is depicted by the eroding cliffs of the Norfolk coast framing the composition. Its detailed brushwork includes stars and the ocean, perhaps the most common of all symbols of the unconscious psyche. Protozoan marine-life, animals and ageing humans are also depicted in a skilfully layered composition evoking the cosmic nature of time. It's a canvas lush in colouration which instantly transports the viewer to internal landscapes of the imagination where as in much of Peter Rodulfo's art, imagery, technique and imagination coagulate to form an absorbing viewing experience.

In January 2012 Peter Rodulfo released no less than twelve photographic images of new paintings to public view. I've chosen just two of his paintings from a total of over 60 in his facebook portfolio for 2011/12 alone. With such a varied and expansive back-catalogue and with many paintings quite different in subject-matter, but equal in terms of technical virtuosity, its well worth checking out more of Rodulfo's art-work.

An Intruder in the Forest by Rodulfo.

See also -

Rodulfo's Mandala of Loving-Kindness

more of Peter Rodulfo's paintings here

Wikipedia entry for Peter Rodulfo

As the elephant laughed - A panorama of evolutionAn Intruder in the Forest by Rodulfo.

See also -

Rodulfo's Mandala of Loving-Kindness

more of Peter Rodulfo's paintings here

Wikipedia entry for Peter Rodulfo